The year 2023 has seen China grapple with high-profile geopolitical tensions, post-pandemic economic headwinds, and societal strains. But in the background, the world’s most populous nation is also wrestling with an intensifying environmental crisis. This past year, China set new records for extreme temperatures, faced the heaviest rains in over a decade, and worked to combat the worst droughts in 60 years. The very stark reality for China’s leaders is that the intensifying effects of climate change potentially threaten both the stability of the country and the longevity of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule.

China’s domestic response to date has prioritized measures to adapt to climate change over its efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Effective adaptation measures require experimentation and tolerance for risk and failure. However, increasing centralization throughout the Chinese system and its penchant for centrally directed and over-engineered solutions threaten the country’s capacity to adapt to rising temperatures.

Western media commentary often focuses on actions to mitigate climate change — that is, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions — and casts climate change mitigation as a global challenge in which the United States and China are the two most critical players. That framing is justified, especially as the United States and China are the largest greenhouse gas emitters, with China’s emissions exceeding those of all developed countries combined.

Beijing has consistently insisted that advanced industrial nations should shoulder the lion’s share of mitigation responsibilities because their historical carbon emissions have significantly exhausted the world’s carbon budget. China believes later-industrializing nations should not bear the brunt of the bill.

Adaptation over mitigation

Unlike its Western counterparts, though, China’s climate change policies have since the early 2000s accorded greater priority to adaptation than to mitigation. Consequently, its key mitigation targets, to peak greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, are not very ambitious given its ability to focus resources and centralize decisionmaking and implementation.

The central prong of China’s strategy to deal with climate change springs from an assessment that, regardless of any mitigation efforts China makes, the People’s Republic of China will still have to cope with temperatures rising well above the 1.5 degrees Celsius peak embodied in the Paris Agreement and its subsequent iterations. This explains China’s prioritizing adaptation to a warming world. But Beijing does not officially tout its adaptation efforts as necessary to deal with looming domestic environmental crises. It apparently does not want to sow pessimism about the future and increase popular pressure on the CCP to achieve heroic environmental results.

Instead, as Eyck Freymann has elaborated in an insightful series in The Wire China, China frames its adaptation efforts using the relatively optimistic sounding phraseology of promoting “ecological [i.e., adaptation to climate change] civilization” and “ecological security,” with the rhetorical goal of enhancing sustainable harmony between humans and the natural environment. Behind this feel-good terminology is a series of adaptation plans, policies, and projects that are startling in their scope and objectives. As Freymann details, these efforts include “constructing the largest water transfer system in human history; expanding and raising nearly 6,000 miles of sea walls along its coasts; building a strategic grain reserve larger than the rest of the world’s combined; carving wetland flood basins in the centers of its largest cities; restoring coastal wetlands to act as buffers against storms; and relocating hundreds of thousands of ‘ecological migrants’ in low-lying areas.”

These projects and more are the products of major plans and policy documents, including Jiang Zemin’s introduction of the term “ecological security” (2006); a 2014 plan to have 80% of China’s cities build the capacity to collect and recycle 70% of their rainwater by 2030; the National Plan for Seawall Construction (2017); the National Strategy on Climate Adaptation 2035 (2022); Xi Jinping’s July 2023 announcement of a major program to maximize the use of arable land for growing staples and promote technology to revolutionize agricultural sustainability in a changing climate; and the list goes on.

China’s adaptation playbook essentially relies on an engineering approach to dealing with climate change’s growing impacts. Xi rightly views China’s political economy as exceptional in its ability to, inter alia, mobilize vast resources to build infrastructure, change land use patterns, implement focused industrial policies, relocate large populations, and direct funds and human resources to critical research and development priorities.

Living with floods and drought

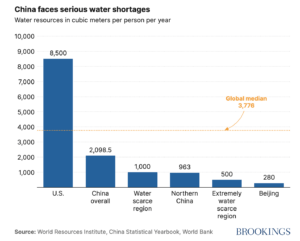

Water issues pose the gravest national challenges, and the regime’s responses reflect both its underlying strategy for adapting to a warmer climate and the political economy undergirding that effort.

Major east coast industrial centers are highly exposed to flooding from rising sea levels. Southeastern China suffers from increasingly frequent floods and storms, while the southwest has in recent years faced both unprecedented floods along the Yangtze River and extraordinary heat and drought that at times threatened the viability of massive hydropower plants whose output provides electricity all the way across to the east coast. The glaciers along the Hindu Kush and Himalaya range, often called the “water tower of Asia,” are a key source and regulator of water flows to the major rivers that traverse central and southern China, and these glaciers are now melting at a frightful pace.

Northern China is overall extremely water scarce, with most of its territory qualifying as highly stressed. In response, Beijing has launched a South-to-North water transfer project that is the largest such effort in human history. This project to date has produced two major channels to bring water from eastern and central sections of the Yangtze River to the Beijing/Tianjin area in Hebei province. A third route in China’s far west will divert water from a tributary to the Yangtze to the Yellow River. Dams, water treatment facilities, pumping stations, and other infrastructure are costing tens of billions of dollars, even as the environmental impacts on the Yangtze River itself and along the diversion channels are still only poorly understood. Beijing’s ultimate goal is to be able to move water as needed when climate-related disasters occur in a world that has warmed well over 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Investing in clean energy

Alongside its ambitious adaptation efforts, Beijing also is investing significantly in developing clean energy technologies and related products. Such investments have not been driven solely by carbon mitigation concerns; Beijing envisions China becoming the indispensable global provider of these pivotal technologies, reaping both financial and geopolitical benefits. This is the second prong of China’s climate strategy: to make the world dependent upon China for the clean energy transition. Put differently, having paid a very high historical price for lagging behind the West in the industrial revolution, Beijing now seeks to be the global leader in the clean energy revolution.

In sum, China is highly vulnerable to climate change and is very focused on creating the conditions to sustain a viable society with the expectation that it will face temperatures that have risen well above 1.5 (or even 2.0) degrees Celsius in the second half of the 21st century. Its most critical climate-related efforts, such as the South-to-North water transfer project, seek to engineer viable solutions to the impacts that will in the coming decades otherwise destabilize Chinese society; severely impact the country’s economic, health, and security systems; and thus potentially threaten the basic viability of the existing political system. While China touts the goals it has set for mitigation, its greenhouse gas targets are not terribly ambitious, even as it is vigorously pursuing its strategy to become a globally indispensable source of clean energy technologies and the products that incorporate them. Nobody can foresee how all of this will play out.

Centralization and the challenges of adaptation

Because China’s domestic climate challenges are so massive, it is necessary, when thinking about the future, to consider how changes over the past decade and more in China’s policymaking and implementation and state-society relations may affect the country’s adaptation programs. For the very strengths of this system also expose its Achilles’ heel. Xi’s centralization of decisionmaking and his focus on domestic security are sharply constraining civil society, shrinking the space for initiatives tailored to the distinctiveness of local regions, limiting criticism of higher-level policies that might prevent major misjudgments, and disincentivizing the practice of passing bad news up the political hierarchy.

Effective adaptation to climate change requires major national initiatives, a vibrant civil society, and a great deal of latitude for local decisionmaking, debate, and experimentation. This is especially true in a country as large, lacking in natural resources, and ecologically, economically, and socially diverse as China. Therefore, Beijing’s turn toward increasingly centralized decisionmaking may, ironically, create greater obstacles to achieving China’s goal of adapting successfully to a world that is subject to the most severe consequences of climate change than is currently appreciated.

The question now is whether the CCP apparatus can reform its adaptation methods to allow greater systemic flexibility to effectively deal with the rapidly increasing domestic impacts of climate change. If China’s leaders do not modify their current decisionmaking and policy implementation practices, they will risk falling critically short in addressing the threats posed by climate change.