BLOG

December 11th, 2017

Via Bloomberg, a report on Cape Town’s water crisis:

Cape Town Mayor Patricia de Lille says she has a new reason to hate Mondays.

That’s when she gets weekly reports on levels in the dams that supply South Africa’s second-biggest city, and on how much water its 4 million residents are using. The numbers regularly show that “Day Zero”—when most taps could stop running—will probably arrive in May, a month or two before the onset of the winter rains.

“We have to change our relationship with water,” said De Lille, who has filled in her swimming pool and stopped washing her car. She spends 70 percent of her working day dealing with the crisis. “We have to plan for being permanently in a drought-stricken area,” she said in in her office on the sixth floor of the Cape Town civic center.

Cape Town, whose lush, stunning setting induced explorer Francis Drake in 1580 to call it “the most stately thing and the fairest cape we ever saw,” risks running dry. The severity of the crisis, brought on by three years of poor rains and surging water demand, is highly unusual even at a time of climate extremes, said Bob Scholes, a professor of systems ecology at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

“Running out of water in places that have a highly developed water infrastructure is not that common,” he said. “I know of no example of a city the size of Cape Town running out of water. It would be quite catastrophic.”

The water shortage has become staple dinner-table and radio talk show conversation, and a Facebook group on how to save water and prepare for outages has drawn more than 121,000 followers. Rainwater-tank suppliers and borehole companies are doing a roaring trade as those residents who can pay seek to reduce their reliance on the municipal grid.

Massmart Ltd.’s building supply chain Builders Warehouse, which sells the tanks, and driller De Wets Water & Boreholes both have waiting lists of at least six months.

It’s an alarming development for a city that draws millions of tourists a year to its sandy beaches, iconic flat-topped Table Mountain and picturesque wine lands. Before he became president after the end of apartheid, Nelson Mandela was jailed on a small island just off its coast for 18 years and spent another nine years in its mainland prisons.

In a bid to curb consumption, the city has banned residents from watering their gardens and washing their cars, shut most public swimming pools and cut the water pressure, causing intermittent outages in some high-lying areas and tall apartment buildings. The city’s poor, who are wholly dependent on the municipal supply and have limited space to store water, have been the hardest hit.

Patricia Gxothelwa, 34, an unemployed resident of Imizamo Yethu township, about 12 kilometers south of the city center, has to use a bucket to collect water from communal taps a short walk away when the supply is cut off from the hillside shack she shares with her husband and four children. It’s an increasingly regular occurrence.

“Sometimes they cut our water off for two or three hours,” Gxothelwa said as she gestured toward her single inlet pipe. “It’s more than before, once or twice a week. Water is one of our biggest problems.”

Three straight years of poor rains typically occur less than once in a millennium, according to University of Cape Town climatologists Piotr Wolski, Bruce Hewitson and Chris Jack. It’s unclear what’s caused such extreme drought, though climate change is a possible factor and the city should brace itself for a recurrence, they said in a study published Oct. 6.

A 50 percent increase in Cape Town’s population over the past decade has added to the pressure on the water supply. The city has drawn new residents from the Johannesburg-Pretoria area, drawn by the slower-pace seaside lifestyle, and from the neighboring Eastern Cape region, where there are fewer job opportunities.

Also hindering efforts to respond to the crisis: A lack of coordination and cooperation between the African National Congress-controlled national government on the one hand and the city and surrounding Western Cape province, run by the main opposition Democratic Alliance, on the other. Appeals to have the entire Western Cape declared a disaster zone went unheeded for months and the national water department, which is responsible for bulk supply, has exhausted its budget, according to Helen Zille, the provincial premier.

“The city responded quite belatedly to some of the signals for various reasons, some of which may be not wanting to lose voter confidence, delays with tendering processes and not wanting to invest in projects unnecessarily,” said Martine Visser, a professor and behavioral economist at the University of Cape Town who’s been advising the city. “But when you look at the drop in consumption, particularly among high-income households, then I think they have been quite successful.”

While average daily consumption has plummeted to about 600 million liters (158 million gallons) of water a day from 1.1 billion liters a year ago, about half of households still aren’t adhering to the city’s usage targets. About 19,000 homes that have regularly exceeded their recommended quotas have had mandatory devices fitted to their inlet pipes that restrict them to 350 liters a day.

Besides trying to curb usage, the city is also rushing to augment water supply from the rain-fed dams by tapping underground aquifers, springs and boreholes, and is fast-tracking plans to build several desalination plants.

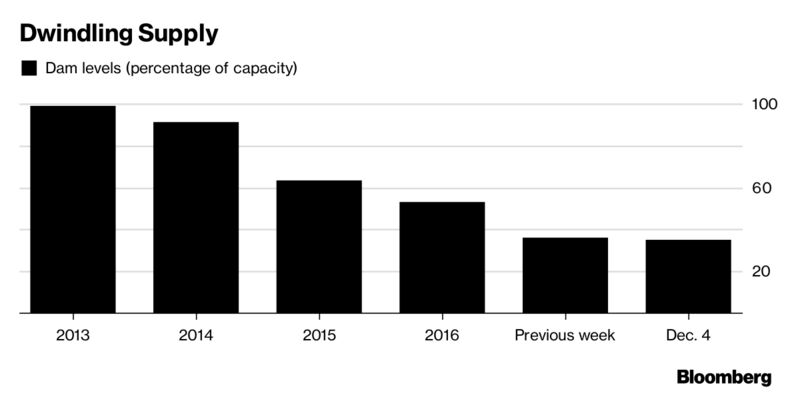

De Lille says she’s is confident the city can avoid Day Zero, which will occur if dam levels hit 13.5 percent (they are currently at about 35 percent, down from 53 percent a year ago and 92 percent in 2014). But contingency plans are being put in place for that eventuality. They include distributing drinking water at 200 collection points, guarded by the police and army, and rationing residents to 25 liters each.

“I don’t want to underestimate how catastrophic Day Zero could be,” said Clem Sunter, an independent scenario planner who has also been advising the city. “It would require thousands of tankers to provide a minimal level of water to each person. You would have to think of temporarily evacuating people.”