Amid growing Western pressure and changes throughout Eurasia, regions that were once considered on the Eurasian periphery are now gaining significance. Chief among them is Central Asia, a region that was historically considered part of Russia’s sphere of influence and is today emerging as a key territory connecting major players like Russia, Iran and China. But one critical issue is increasingly hampering the political ambitions of Central Asian countries: water.

Origins of the Problem

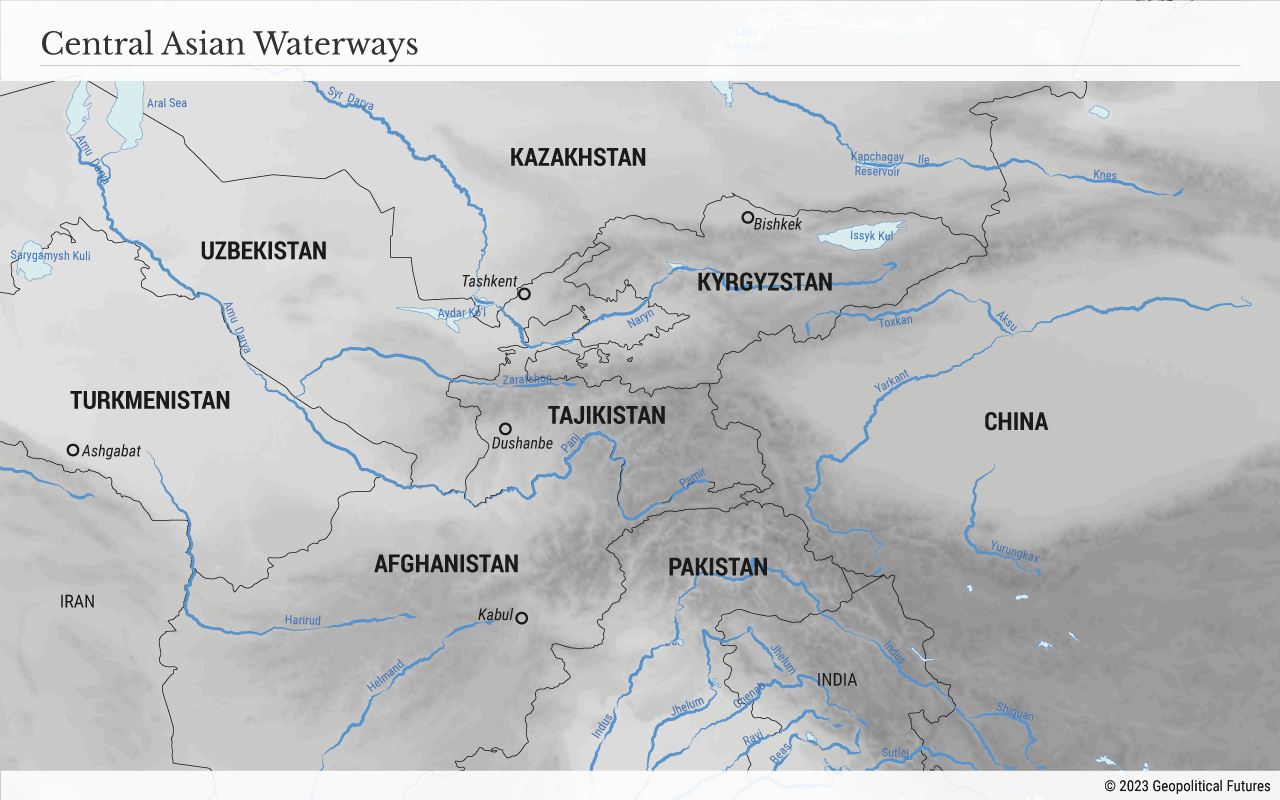

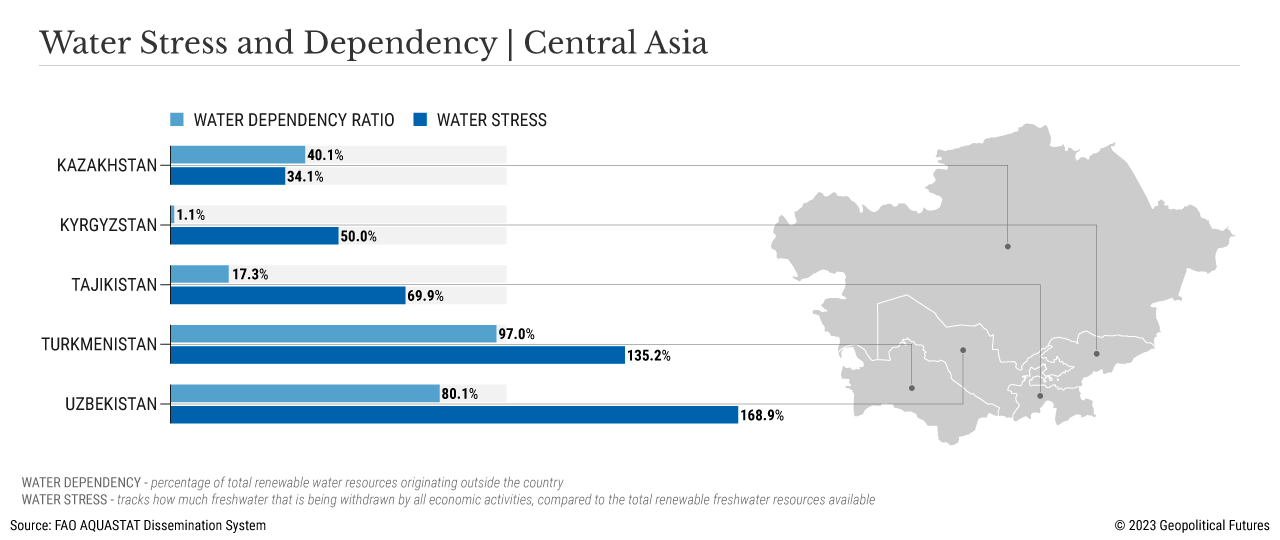

Central Asian states can be divided into two groups: water-rich countries (Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan) and water-dependent countries (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan). Most water deposits in the region are formed by melting snow and glaciers from the mountains. The two main rivers that flow through the region, the Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya, provide water for domestic, agricultural and energy use.

But these sources are proving increasingly insufficient. Central Asia has been facing a serious water deficit for several years for several reasons. The first is climate change, which is causing glaciers to melt faster than before, decreased snow cover in the Tian Shan and Pamir-Alay mountain ranges and declining water levels in lakes. Second, outdated infrastructure, including Soviet-era industrial facilities and water management systems, is leading to water loss. In Uzbekistan, for example, 40 percent of water loss is due to poor infrastructure. This second is the mounting tensions between the former Soviet states over how to manage resources. In the Soviet era, Moscow managed the irrigation system for the entire region. After gaining independence, Central Asian countries initially supported the idea of sharing water that flowed through transboundary rivers – which was reinforced by a number of regional agreements. But gradually they began to prioritize their own self-interests. Thus, when water-rich Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan experienced serious energy shortages, they sought to boost domestic production using water, which directly affected downstream countries. Their decisions to build hydroelectric power plants were met with anger in downstream states, which were concerned that such projects would deplete their own supplies.

The third problem is the increasing demand. According to U.N. estimates, the population of the region has grown by 50 percent since the 1990s (from 52 million to 78 million) and is expected to reach more than 100 million by 2050. Water is also needed for irrigation in the agricultural sector, which accounts for up to 15 percent of the Kyrgyz economy, 27 percent of the Tajik economy and up to 26 percent of the Uzbek economy. Hydroelectric power, which accounts for nearly 90 percent of energy in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, is also a growing consumer of water resources.

Meanwhile, the Qosh Tepa irrigation canal in northern Afghanistan is a concern for Central Asia. It aims to transform the country’s agricultural landscape but could cut off supplies from the Amu Darya River to Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, which could lose up to 15 percent of their flow from the river when the waterway is completed in 2028.

These factors explain why even upstream Kyrgyzstan is facing a shortage this year. On Aug. 1, Kyrgyz authorities declared a state of emergency in the energy sector that will run last until the end of 2026. Earlier this month, the country stopped supplying irrigation water to Kazakhstan due to declining supplies from the Kirov reservoir, which now receives only 1.3 cubic meters per second compared to 13.7 cubic meters per second in 2022. Kazakhstan’s own water shortage threatens irrigation and drinking water supplies, which have resulted in small protests. This week, a state of emergency was declared in six districts of the southern region of Zhambyl due to heat waves and water scarcity. Crop losses this year are expected to increase by 25-30 percent from last year because of the lack of irrigation water and high temperatures. People in Uzbekistan also say they have been forced to conserve water and stagger their usage.

Geopolitical Implications

These issues have implications for Central Asia and beyond. Crop damage from insufficient irrigation is a major concern for the agricultural sector, as well as consumers who could face rising food costs. This could lead to social unrest as populations grow frustrated with spikes in prices for food, energy and utilities. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, which rely on food for 20 percent and 10 percent of their total exports, respectively, could see reduced export earnings. Poor quality and inadequate water supplies could also help spread diseases.

As economic and environmental conditions deteriorate, populations could begin to migrate. Rural areas, which account for more than half of the Central Asian population – and which are often low income – could see declining numbers as people grow wary about the state of the agricultural sector and their own livelihoods. The World Bank projects that the number of climate migrants in Central Asia could reach 2.4 million by 2050. Those who choose to leave their homes will be concentrated along Kazakhstan’s southern border, areas surrounding the Ferghana Valley and areas around Bishkek due to declining water access and crop quality. These populations are most likely to move to Central Asia’s neighboring countries (especially Russia and China) in search of work, housing and a better life, which could have security implications.

Conflict between the countries of the region is also a possibility. In 2022, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan saw violent clashes over access to water and land along their border, which hasn’t been fully demarcated. This week, Kazakhstan blocked Kyrgyz vehicles from entering the country after Kyrgyzstan announced that it would reduce water supplies to Kazakhstan. Kyrgyzstan says the Kazakh move violates Eurasian Economic Union rules on the free movement of goods and undermines the authority of the bloc.

Indeed, the water issue could complicate regional relations, cause friction in regional alliances, and disrupt trade, infrastructure projects and military operations. And as Central Asia’s importance as a transit route and provider of energy and resources grows, these disruptions will have implications beyond the region. Russia and China, in particular, would incur potential economic costs if the region destabilizes. They don’t want to see the EAEU and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization undermined because of disputes over water.

Major players understand that they will have to invest in resolving this issue if Central Asia is to play a significant role in the geopolitics of the region. Thus, the Kyrgyz government earlier this month signed an agreement with Chinese firms on the construction of multiple hydroelectric power plants, which will help generate more energy while reducing water loss by developing more modern infrastructure. Central Asian countries are also likely waiting for proposals from Russia, such as reviving the Soviet-era project of transferring water from Siberia to Central Asia. This case shows that long-standing problems in peripheral regions increasingly have the potential to reach major Eurasian powers.

BLOG

Water: A Barrier to Central Asia’s Rise?

August 23rd, 2023

August 23rd, 2023

Via Geopolitical Futures, a look at how Central Asia’s growing role could be hampered by a long-standing problem – water scarcity:

This entry was posted on

Wednesday, August 23rd, 2023 at

3:22 am and is filed under

Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan. You can follow any responses to this entry through the

RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

© 2024 Water Politics LLC . 'Water Politics', 'Water. Politics. Life', and 'Defining the Geopolitics of a Thirsty World' are service marks of Water Politics LLC.