BLOG

October 27th, 2016

Via Global Risk Insights, commentary on the escalating India-Pakistan tensions surrounding Kashmir, in which New Delhi has not ruled out the possibility that it will abrogate the longstanding Indus Waters Treaty:

Recent months have witnessed a dramatic escalation of tensions between India and Pakistan in relation to events in the Kashmir region. The historic standoff between the two states took on a heightened level of intensity in July, following Pakistan’s expressed support for protests against the death of Burhan Wani, Kashmir independent activist, at the hands of Indian security forces. Relations have been further soured by the events of 18 September, when at least 17 Indian soldiers were killed in an attack on a military base in Indian-controlled Kashmir. India blames the attack on a Pakistan-based militant group, a claim that has been refuted by Pakistan.

In the furore of diplomatic back-and-forth that has followed – from India’s ‘surgical’ military strikes in Pakistan-controlled Kashmir, to the Pakistani Government’s prohibition of Indian films in cinemas – one threat mooted by the Indian Government is that it may even consider abrogating the longstanding Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) unless Pakistan demonstrates that it is doing more to stamp out terrorism.

Key statements have been made by government officials in India. The Ministry of External Affairs spokesman, Vikas Swarup, suggested that the IWT “cannot be a one-sided affairs”, whilst Narendra Modi made the ominous statement that “blood and water cannot flow together”. In addition, India has reportedly put a stop to future meetings between the two countries’ Indus commissioners.

What is the IWT?

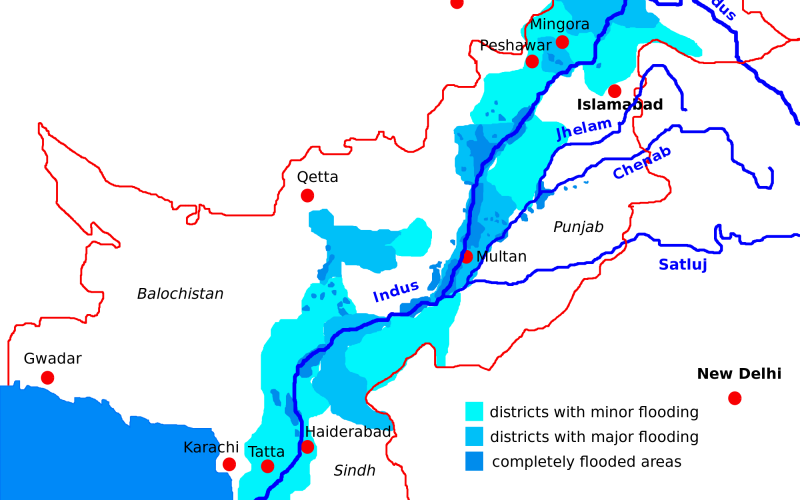

The IWT, a bilaterial agreement between India and Pakistan, addresses water-distribution across the six rivers of the Indus Basin; the three eastern rivers of Ravi, Beas, Sutlej, the three western rivers of Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, and all respective tributaries.

Importantly, India is the ‘upper riparian’ state of the Indus Basin, meaning that its waters first flow through its territory before reaching Pakistan. Under the IWT, however, India’s access is restricted to the waters of the three eastern rivers. Apart from certain specified exemptions, New Delhi is under obligation to let the waters of the western rivers flow through to Pakistan, which accounts for around 80% of the water running from the Indus Basin.

The IWT has been in place in 1960, when agreement was finally reached following negotiations throughout the 1950s. The agreement was brokered by the World Bank, with strong support from the United States and Britain, for whom it was seen as a means of addressing Indo-Pakistani hostility – then a perennial problem facing Western foreign policy in South Asia. Whilst current events are testament to the fact that the IWT did little to reconcile the neighbouring states, it is nevertheless notable that the treaty has survived all subsequent periods of tension and conflict.

Possible consequences of abrogation

In the period following the Modi regime’s suggestion – abrogation of IWT is not off the cards – great deal of polemical debate has taken place between observers in India and Pakistan regarding the potential outcome of such a move. If Indian commentators have tended to underplay the potential fall-out, their Pakistani counterparts have jumped to the other extreme. Polemics aside, however, it is possible to identify a number of fairly straightforward potential consequences.

It is, of course, India’s position as the upper riparian state of the Indus Basin that gives particular meaning to its suggestions to abrogate the IWT; the threat to revoke the IWT is tantamount to a threat to prevent water flowing to Pakistan. As officials in both states will be aware, the consequences of such a move are potentially devastating for Pakistan. Like India, Pakistan suffers from chronic issues of water-stress, and certain areas of the country, such as Sindh province, are heavily dependent on Indus Basin waters. If access to this water was reduced or cut off, it could have dramatic economic implications for the country.

However, a move by the Modi regime to block the free flow of water through the Indus Basin could also have implications for India. On a practical level, one local expert has recently observed that India does not actually poses the necessary infrastructure to store or make use of the additional water it might accrue. This would require storage dams and diversion canal network on a scale that would take years to construct. Preventing waters from flowing to Pakistan could even cause flooding in Indian-controlled parts of Kashmir.

Violation of the IWT could potentially backfire on India in other ways. Under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), China has significant investments in parts of Pakistan that could well be threatened by a sudden shortage of water. An Indian abrogation of IWT could therefore run directly against Beijing’s interests. The implications of upsetting Beijing in this way would be particularly acute: just as India is the upper riparian state of the Indus Basin, China is upper riparian to India’s Brahmaputra River.

If direct retaliation from China is a potential consequence, so too is the potential to undermine the spirit of cooperation that has characterised international water policy in South Asia. The IWT is generally considered a model for water-distribution agreements and India has similar, well-functioning treaties in place with Bangladesh and Myanmar. A move to undermine the IWT could lead to the unravelling of this framework.

Will it happen?

There are thus a number of reasons why India may be reluctant to follow through on its threat regarding IWT. Moreover, New Delhi will also be wary of potential charges of hypocrisy were it to take such a course. Since its election in 2014, the Modi regime has been at pains to present itself to the international community as an abider of the international rules, juxtaposing, for instance, its ‘utmost respect’ for the judgements of the Permanent Court of Arbitration against Beijing’s unilateral approach towards the South China Sea. To most impartial observers, then, all this would appear to suggest that the potential consequences make it unlikely that India’s IWT threat will materialise.

That said, there are two possible developments that could provoke India to act. Most obviously, another attack on Indian forces could well convince its policymakers that breach of IWT is worth the risks. Not unrelated to this, India’s actions could also be steered by the level of pressure exerted upon the Government domestically. After all, whilst the image that Modi has sought to present to the outside world is one of peaceful cooperation, his Bharatiya Janata Party nevertheless ascended to power on the back of increased Hindu nationalism that demands a hard-line approach towards Pakistan. With important provincial elections looming in early 2017, heightened pressure from the domestic Hindu right could push the Modi regime into an act of political muscle-flexing that it might not otherwise undertake.