We’re seeing not just being at the table,

but actually having an influence on the agenda.

We’re looking at the next step – because you can have

a seat at the table, but not be taken seriously.

And tribes, especially now in regards to water,

we have to be taken seriously.– Stephen Roe Lewis, Governor Gila Indian River Community

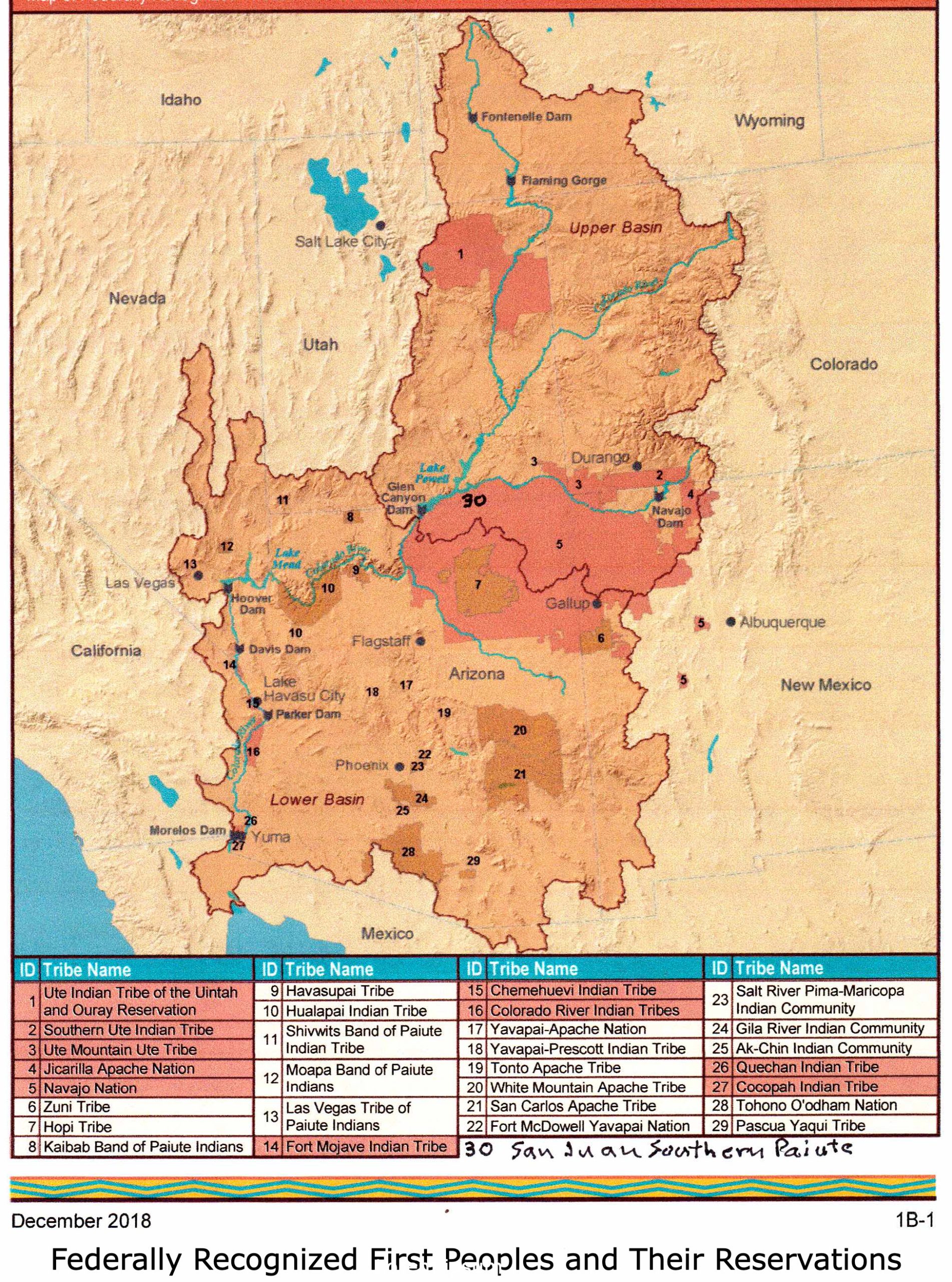

If you are following the ever-unfolding sagas of the Colorado River in the 21st century, the Early Anthropocene, you are probably aware that there are water-related issues with the 30 remaining First Peoples living within the Colorado River Basin.

I’ll say, to start, that I don’t like to call the 574 recognized First Peoples in the United States and Alaska ‘Indians’ (colonizing and homogenizing term, inaccurate too), ‘American Indians’ (two Eurocentric colonizing words), or ‘Native Americans’ (anyone born here is a ‘native’). I prefer to think of them as ‘First People’ for a couple reasons. First, because many of the groups tend to call themselves ‘the people’ – Dine’e, the name the Navajos give themselves translates as ‘the people.’ Navajo, on the other hand, is from a Tewa People word meaning ‘planted field,’ hardly descriptive of a people still ambivalent about farming as a way of life. The Apaches call themselves Ndee, which translates as ‘the people’; but Apache is from the Zuni People’s word for ‘enemy.’ Just as Comanche comes from a Ute People’s word for ‘one who fights with me,’ while to themselves the Comanche are the Numinu, which translates as – you guessed it: ‘the people.’ These are more precise and intimate designations than ‘we the people’ in our constitution.

A second reason for calling them the First Peoples is to remind myself that they were in fact here first. They were not ‘civilized’ enough to understand the fundamental holy sanctity of private property, money, or anything else held sacred among the civilized people that overran them. Had they understood those things, and had prior appropriation doctrines in place, and the unified capability to enforce such doctrines, as we try to have in place now for selecting our immigrants – and also had a medical establishment capable of developing vaccines against strange microscopic invaders – then the history of the European Expansion into America would probably have been a little more humble than it has been. And the recent histories of the First Peoples, the people here first, might have been less traumatic and tragic.

This is a relevant topic at this point since the remaining First Peoples in the Colorado River region have made the mainstream news, at least in the West, twice just recently on water-related issues. One was a decision by the Red Meanies that are now the voice of The Supremes, singing their chorus on the power of power; they declared that, while the federal government acknowledges that the Navajo People are entitled to water for their reservation, the 1868 treaty with them contains no explicit responsibility to ‘act affirmatively’ in helping them develop or even lay claim to that water.

The other news story was reported from a conference at the Getches-Wilkinson Law Center at the University of Colorado in Boulder; 13 leaders from the 30 remaining First Peoples on reservations in the Colorado River Basin took the stage in a panel to convey the message that they will participate in the negotiations getting underway about the management of the Colorado River and its waters after 2026 and the expiring of the ‘Interim Guidelines,’ which are now proving as ineffective as the Colorado River Compact they were created to supplement.

There is, as usual, a lot more back story to these things than makes it into the news. And without at least some of the back story, the news stories make less sense. One thing to keep in mind is how ‘distinct’ the remaining 29 First Peoples in the Colorado River Basin are (like most of the 574 recognized First Peoples in the United States and Alaska). While the officially registered populations of each of the First Peoples range from a few hundred members to hundreds of thousands, each People has its own culture – an internal economy and polity that is more likely to be socialistic than individualistic, animistic spiritual practices that are closely associated with their living environment, a higher ratio of familial education (father to son, mother to daughter) to formal schooling, and often a unique language for only a few thousand people, or variations on a language common to several Peoples in the same region. These groups historically communicated with each other, traded with each other, and occasionally fought each other. Some who shared the same or similar languages would winter together in big encampments – one consequence of which was keeping their gene pools healthy with new input, new husbands usually joining their wive’s clans. But despite such interactions, they also retained their unique and distinguishing cultural characteristics. Many of these cultures are similar in their fundamentals, but they make serious efforts to retain the elements that distinguish them. These unique and passionately maintained distinctive cultures have been difficult for us dominating e pluribus unum Euro-Americans to comprehend and accept.

Adding to that difficulty is the extent to which the First Peoples throughout the Colorado River region were, at the time of contact with Euro-Americans, at different stages in adapting to the ‘trauma of success’ – the population expansions that occurred globally as the harsh Pleistocene climate mellowed into the warmer, wetter, more life-supporting Holocene interval. Expanding hunter-forager populations needed more territory.

That territorial tension was resolved – or not resolved – two different ways by the First Peoples, as it had been millennia before in Europe and western Asia. Some of the Peoples developed a culture of conflict with neighboring Peoples, cultivating warrior cultures engaged in fighting and raiding – as Steven LeBlanc documented in his Prehistoric Warfare in the American Southwest. Other Peoples gave up the hunter-forager life and transitioned to agriculture, concentrating their food plants and animal herds where they could be protected against the raiders. This also concentrated and stabilized the way they lived, the kind of structures they built to live in, the kinds of trading and commerce they engaged in. And pressure from the raiding Peoples also shaped the way they lived; some of those early conflicts are remembered in intertribal relations among First Peoples today.

Populations continued to grow, especially with agricultural surpluses, and the ongoing ‘trauma of success’ forced some of the Peoples to develop even more complex socioeconomic organizations for production and distribution of food and other survival goods – what we call the urbanizing ‘civilization’ stage in human culture. Two civilizations-scale cultures developed in the Precolumbian Colorado River Basin: one was the ‘Ancestral Puebloans’ who developed a highly integrated system of villages linked through storing and trading of grain and other resources in the San Juan River valleys, centered in the broad Chaco Canyon. The other was the Hohokam (or Huhugam) irrigation society in the confluence area of the Salt and Gila Rivers in present-day central Arizona. The Hohokam People’s irrigation system had a high degree of sophistication, considering that its irrigation systems were all dug with stick-and-stone tools and baskets. They also had a sizable urban center whose ruins have been preserved in (and dwarfed by) present-day downtown Phoenix.

By the time the Euro-American settlers and unsettlers arrived in the Colorado basin, though, these civilizations, like all historical civilizations globally to this point, had collapsed from their own density, complexity and the depletion of vital resources. Those who survived the chaos of the collapses dropped back to some earlier stage in that cultural evolution driven by population. Some refugees from the Ancestral Puebloans’ Chaco Canyon ‘Interconnect’ left the Colorado Basin and went to the Rio Grande valley to continue farming; others found remote spots in the San Juan tributaries. Several First Peoples from the Hohokam Culture relocated along the Gila, Salt and Colorado Rivers and continued irrigated farming on a small scale.

And because not everyone is temperamentally fit for agriculture, some of the collapse refugees went all the way back to the hunter-forager life – with raiding each other and the agricultural Peoples added to the repertoire. The bands of Utes in the Southern Rocky mountains showed up around the same time that the Chaco Canyon Interconnect was falling apart, and the Apache Peoples in the Arizona and New Mexico mountains expanded following the Hohokam collapse.

And then there were ‘newcomers,’ the Dine’e People, the ones the other Peoples called the Navajo. They were hunter-foragers filtering down all the way from Canada’s over-populating Athabaskan lake region. They began arriving in the Colorado River region about the time that the Chaco Canyon Interconnect began to fail, and were still trickling in till just a few centuries before the Spanish-Americans came into the region. The Navajo brought domesticated sheep with them, and followed their sheep around the valleys and uplands of the depopulating San Juan basin and Colorado Plateau, adapting their hunting and foraging skills in a new environment – and also joining in on the raiding that had become part of that way of life.

So the Euro-Americans encountered almost the full spectrum of human cultural evolution when they arrived in the Colorado River basin, except for an active civilization. They found primal First Peoples like the Cocopah down in the delta and some of the southern Great Basin Paiutes on the Colorado Plateau, still primarily hunting and foraging but also beginning to practice some basic agriculture. There were also post-civilization First Peoples like the Salt River Pima-Maricopa, the Gila River and the Colorado River Peoples with long histories of desert agriculture, and there were both pre- and post-civilization hunter-forager-raiders.

The European Expansion came to the Colorado River region first from the south, where Spanish invaders had conquered civilized Aztec Mexico early in the 16th century; exploratory parties went northward in search of gold and silver and laid claim to everything up to around the 40th parallel, but only really settled – and unsettled – in the middle Rio Grande valleys and California. Their interest in the First Peoples they encountered was limited to whatever material wealth they could commandeer in the name of the King; they did not appear to see the people themselves as fellow humans, but as simple savages to convert and enslave.

The First Peoples they encountered, on the other hand, became very interested in the horses the Spanish brought, some which went feral and, along with European germs, spread out ahead of the Spanish. The hunter-forager-raider Peoples quickly developed a horse culture and expanded both their range and their daring; they began to harass the new white settlers as well as each other.

The Spanish Americans lost their El Norte empire in the 1846-48 Mexican War, which opened the whole Southwest up to the larger Euro-American westward expansion. The Spanish had wanted the First Peoples as slaves; the Euro-Americans just wanted them out of the way. Skirmishes between the warrior/raiders of the First Peoples, armed at first with stone age weaponry, and the heavily armed U.S. Cavalry escalated into a multi-fronted three-decade war from the end of the Civil War to nearly the turn of the 20th century.

From the perspective of many prominent 19th-century western leaders – like Col. John Chivington, Methodist minister, Masonic Grand Master, and leader of 300 volunteers in the Sand Creek Massacre – genocide would not have been too strong a word for their objective; they wanted to rid the land of those who were there first and in the way of their Manifest Destiny to subdue the continent. Cooler heads prevailed in Washington, however, and the ultimate objective of ‘Indian policy’ came to be forced assimilation: instead of ‘kill the Indians,’ it was ‘kill the Indian, save the man (woman or child).’

The First Peoples one by one accepted ‘offers they could not refuse,’ to give up most of their traditional territory in exchange for a much smaller reservation, peace, and generally vague promises of federal assistance ‘to change their habits and to become a pastoral and civilized people’ – which some of them already were, perhaps moreso than many of the Euro-Americans.

To facilitate that assimilation, children as young as six were taken from their families and sent to boarding schools where they were forbidden to use their native language, and were schooled in becoming good industrial workers. To teach a proper respect for private property, the Dawes Act in 1887 broke up the reservations into 160-acre ‘homesteads.’ Programs were implemented to pay for the relocation of individuals and families to cities. Only the vast scale of the West and the limited number of policy enforcers for the numerous reservations enabled the First Peoples to keep their own cultural fires banked but burning.

This policy of forced assimilation prevailed until the 1930s. Current news stories about Colorado River issues have noted with righteous indignation that the Colorado River Compact ‘ignored the Indians,’ but that is not exactly the case; Article VII of the Compact says that ‘Nothing in this compact shall be construed as affecting the obligations of the United States of America to Indian tribes.’ In 1922, the ‘obligations to the Indian tribes’ were still construed to be facilitating their conversion to ‘civilized peoples.’ This essentially meant letting the tribes ‘disappear’ as the First Peoples discovered the blessings and advantages of assimilating into the mainstream culture, which would have negated the question of tribal waters. E pluribus unum.

It is probably important to remember that these assimilationist policies were not conceived and put into force by evil people, but by well-meaning Christians who sincerely believed they were acting in the best interests of the First Peoples; if the First Peoples had to be forced, it was because they were blind to their own best interests. Historically many bad things have come as consequences of good but naive intentions.

This was demonstrated just last month, when the constitutionality of a law intended to shut down one of the assimilationist strategies was challenged in the courts – the Indian Child Welfare Act, which put First People families first in line for adopting orphaned or abandoned First People children. Surely this is racist, was the argument against the Act; isn’t it obvious that it would be better for a child to grow up well provided for in a good middle-class home, rather than left on an impoverished reservation with an aunt or grandparent? The Supremes – a little surprisingly – upheld the Act, 7-2, against the suit brought by several ‘red’ states, but the well-meaning will continue to act in what they perceive to be the best interests of those who were here first.

That is a good place to pause; next post we’ll look at how things began to turn around for the First Peoples – how they themselves worked, and continue to work, to turn things around, and found co-conspirators in the larger society, even in the government. What’s the saying? What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger. And the First Peoples have survived the efforts to kill them, first physically then culturally, and are here to stay – and to be heard on our common future.

Stay tuned for Part 2, when we will look more closely at the Navajo decision, and at some things the First Peoples might contribute to the next chapters in the management of our coyote river.