BLOG

May 25th, 2023

Courtesy of China Water Risk, a new report analyzing a third of global power generation capacity to find that escalating climate risks and rivers running dry can strand sizeable portions of national power generation assets, including sizeable trifecta exposure to water risks across 10 key rivers from the Yangtze, Yellow, Indus, Ganges, to the Mekong (10 HKH Rivers), showing clear national energy security implications for 16 countries from China, India, Pakistan, Laos, Myanmar, Afghanistan, Nepal to Bhutan – there is high energy dependence on single to multiple rivers.

- Almost half of this (865GW) are in the 10 HKH River Basins – this is more than the total GW of the G7 ex-US;

- Over 94% of the 865GW needs water to generate electricity; and

- Almost 330GW or 38% of power GW clustered in 10 basins are located in areas that are arid or already face ‘High’ to ‘Extremely High’ water stress.

Asia is still power hungry but power generation needs water = vicious cycle: “no water” can strand power, which in turn can exacerbate water scarcity. APAC already accounted for nearly half of global primary energy in 2020, yet it is still undergoing rapid development and urbanisation. The ADB projects that APAC energy demand will double by 2030 and since key types of power generation in the region such as thermal power and hydropower require water to generate electricity, demand for water will also rise. According to the IPCC AR6 WG2, under all 2°C scenarios, the energy sector’s share of global freshwater use is projected to increase to almost a quarter by 2050; driven mainly by the rapid increase in electricity demand across developing nations. However, most thermal power assets across APAC are carbon intensive and contribute to rising water scarcity, which in turn can strand existing power assets as well as hamper power expansion. It is thus imperative that we understand Asia’s tight water-energy-climate nexus so that we can make the right energy decisions today for water & energy security tomorrow.

We analysed 1.9TW of the HKH 16’s power generation assets and found trifecta exposure to water risks across the 10 HKH River Basins. Anchored by China & India, the HKH 16 is a significant driver of APAC growth and future power needs – our analysis, based on the Global Power Plant Database, showed that the HKH 16’s 1.9TW accounted for a third of global power generation capacity. As the IPCC AR6 WG2 warned of “consistent decreases in mid-to-end of century thermal power production capacity due to insufficiency of cooling water” with ‘high confidence’ in central, southern and western Asia, we mapped the HKH 16’s power assets to key water sources such as the 10 HKH Rivers that flow from the Hindu Kush Himalayan Water Towers – see “At-a-glance Power Generation in the 10 HKH River Basins”. Our analyses indicate that the power mix should favour less carbon & less water intensive choices due to sizeable trifecta exposure to water risks:

1) 46% or 865GW is clustered in 10 HKH River Basins which are vulnerable to rising climate risks – for perspective this is more than the combined capacity of Brazil, Canada, Germany, Japan & Russia;

2) Over 94% of this installed capacity needs water to generate electricity – of the 865GW, coal dominates with a 60% share, followed by hydropower with 30%; and

3) Already 38% of the 865GW lies in basin areas that face ‘High’ to ‘Extremely High’ water stress or are arid – this means 329GW of power generation (all types) are very vulnerable to rising scarcity in the basin.

National water & energy security across the HKH 16 are tied as rivers running dry can strand sizeable portions of the HKH 16’s national power assets. Our analyses from each basin as well as each country perspectives revealed important regional & national energy security concerns across the HKH 16 which led us to believe that the future of water & energy security are tied for the HKH 16:

• Significant clustering of key power types of the HKH 16 in the 10 HKH River Basins – 73% of the total hydropower capacity of the HKH 16 are clustered in the 10 HKH River Basins, as is 44% of the HKH 16’s total coal-fired capacity – see graphic “Total Exposure of the HKH 16 to 10 HKH Rivers by Power Type”;

• Installed capacity ranges from 9GW on the Amu Darya to 373GW on the Yangtze – 7 river basins house power assets that serve more than one country. The Mekong has power assets that serve 5 countries whereas the Tarim, Yangtze & Yellow’s power assets only serve China – for at-a-glance summaries, please refer to “10 HKH Rivers power Asia” and individual “River Power Factsheets” in Appendix 2; and

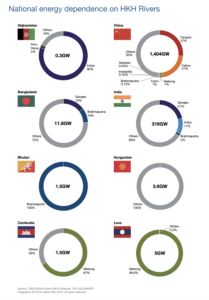

• National energy dependence on singular to multiple HKH rivers – eg. Bhutan & Nepal’s power generation face single key river risk with the Brahmaputra & Ganges respectively; whereas around a third of India’s national power installed capacity are located across 3 rivers and ~50% of China’s national capacity are spread across 7 rivers – more in “National energy dependence on 10 HKH Rivers”.

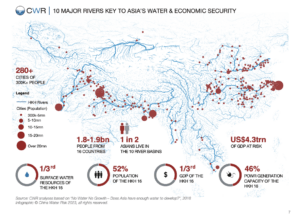

Uncertain future flows of the 10 HKH Rivers puts future water, energy, economic & food security at risk: 1 in 2 Asians + US$4.3trn of annual GDP are also clustered there. In addition to 865GW of power assets, the 10 HKH Rivers Basins also house up to 1.9bn people or 1 in 2 Asians and generate over US$4.3trn of GDP annually across the HKH 16. Yet, components of river flow such as glacial melt, snow/rainfall and monsoon patterns are impacted by climate change posing grave threats to the HKH 16. As our analyses show, although shares may vary by country, the stakes are high across the HKH 16 – see “At-a-glance: water, people, power & the economy”. Future flows of rivers under various climate scenarios must thus also be considered when planning energy expansion/security even for climate scenarios within 2°C: per our NWNG report, a RCP4.5 scenario will result in an overall fall in future river flows (2006-2055) for 4 of the 10 rivers – see “Past 50/Next 50 years = changing water flows”. However, all rivers will face escalating & compounding water risks (chronic & acute) if we are unable to rein in emissions. The transboundary nature of 8 out of the 10 rivers will also lend complexity to managing economic, water and energy security – see “Transboundary issues: not just water sharing but energy policies also”. Curating mountains-to-oceans waternomic roadmaps that include energy policies can therefore help ensure future water, energy, economic & food security across the HKH 16.

The HKH 16 must balance waternomic & powergen risks – especially those in the ‘Overall High Risk Group’. River management is never only about managing water. Balanced power expansion must deliver energy security but not at the expense of water security and economic growth as adding more coal will accelerate climate change and increase water risks. In this regard, waternomic and energy policies will differ by river as well as by country and we have grouped the countries into 4 risk group categories depending on their respective national exposures to the 10 HKH Rivers across various parameters. These include the rivers’ share of national surface water resources plus the shares of national population, GDP, total installed capacity, coal-fired power as well as hydropower capacity that are housed there. It’s worth noting here that half of the HKH 16 fall into the ‘Overall High Risk Group’: Laos, Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Cambodia, Pakistan and Tajikistan – for these, basin risks should guide energy policy. While we’ve provided an overview for each country in this report, it is but a start and deeper analysis by country is needed – for more see “Balancing waternomic & powergen risks across the HKH 16”.

Coal-reliant China & India fall in the ‘Med-High Risk Group’, but play key roles in regional energy & water security as coalfired power is impacted by & contributes to water risk. Despite facing relatively lower risks, China and India have the most amount of GW clustered in the 10 HKH River Basins. Also, they are the two most coal-reliant of the HKH 16. As coal-fired power contributes to and is impacted by rising water scarcity, it is important that China & India (as well as the rest of the HKH 16) choose the right type of power – one that generates more power on less water and less carbon, preferably zero. Here, the IPCC AR6 WG2 recommends shifting to higher shares of renewables such as wind & solar PV to mitigate risks, but note that this doesn’t mean that ‘clean power’ is without water risks (see water risk overviews for hydro, nuclear, solar PV & wind in Chapter 2). Although India & China are aggressively doubling renewables in the next 5 years, our findings show they must do more:

• 97% of the 517GW of coal-fired power located in the 10 HKH River Basins sit in the Yellow, Yangtze, Ganges & Indus – these are key for China & India from economic, population, food & energy perspectives;

• More than half of the coal-fired capacity in each of these 4 rivers face at least ‘Medium-High’ drought risk as well as ‘Medium-High’ flood risk; and

• 188GW or 43% of China’s coal-fired capacity in the 10 HKH River Basins face ‘High’ to ‘Extremely High’ water stress; although India’s fleet is smaller at 55GW, its exposure to severe water stress is higher at 83%.

Picking the right type of power and cooling type can help alleviate water stress but beware of trade-offs! While we need rapid decarbonisation to reduce rising chronic water scarcity risks, we recognise that it may be difficult to completely de-coal from an energy security standpoint. So, for coal-fired plants which are key to support base load and energy security, do maximise energy efficiencies, consider carbon capture and retrofit plants with cooling tech to alleviate water stress in severely water stressed areas. However, key trade-offs must be considered: 1) Carbon capture & storage can be water intensive, so limited water resources can constraint such options; 2) Using dry/air cooling can help alleviate water stress & competition for water, but lower generation efficiencies mean it will result in more carbon emissions and higher costs per unit of power generated; and 3) As extreme weather can cause disruptions in hydropower, more coal-fired capacity may be added to balance the grid and avoid disruption. Indeed, China saw a surge of “just-in-case” coal-fired power additions in 2022 after the severe droughts along the Yangtze. These trade-offs plus more are set out in “Energy policies for a water secure future: 8 broad recommendations”.

Tied energy & water futures = dovetailing of national energy & water security plans. If we do not rein in emissions, the IPCC AR6 warned that 3-4bn people could face chronic water scarcity. As power choices can impact water and the lack of water can strand power assets, water security should decide energy security. However, this is generally not the case at the moment – energy plans are typically prioritised over water security plans and most countries do not even have a water security plan that takes into account the latest climate science, let alone one that dovetails with energy security. The dovetailing of water & energy policies is ever more urgent as escalating & compounding water risks as well as the rising demand for water will bring about more competition for water resources. Indeed, extreme weather is already wreaking havoc: last year, over 30mn people lost their homes to devastating floods in Pakistan; its economy took an estimated 10% hit. At the same time, Yangtze droughts disrupted not just China’s power supply but also global supply chains. While there’s no one-size-fits-all policy, we’ve shared “Lessons from China” in Appendix 1 from cooling tech bans, waternomic roadmaps to managing water extremes.

High stakes = Asia has no choice but to step up & lead global decarbonisation. Although this report only analysed power assets within the 10 HKH River Basins, in reality, all carbon intensive power assets in the HKH 16 and beyond will impact the water & energy security of the HKH 16. Given that the global momentum to reduce emissions has stalled with the Russia-Ukraine war triggering an oil boom, Asia must step up to fill the leadership vacuum. The HKH 16, with heavyweights China and India, can pave the way to balance the ever-rockier geopolitical landscape and steer us away from >4°C of warming under the IPCC SSP3 “Regional Rivalry Scenario”. In developing Asia, we have the luxury of real time adjustments to our development models to rein in emissions plus build infrastructure to adapt to climate impacts. We must grasp this opportunity to fast track the transition as well as prepare and adapt for escalating water risks. We are optimistic that this is possible; for perspective, China’s clean electricity output of 2,960TWh in 2022 already surpassed the EU’s 2021 total electricity generation of 2,785TWh. So while this report is far from perfect, with clear gaps, we felt compelled to make a start in unpacking the nexus. We all have a part to play and we invite all stakeholders to build & improve on the analyses so that we all can better inform & shape our shared energy & water futures. Now is the time for Asia to put in place sensible energy policies that will protect and not destroy our rivers. If we do not fail our rivers, our rivers will not fail us.