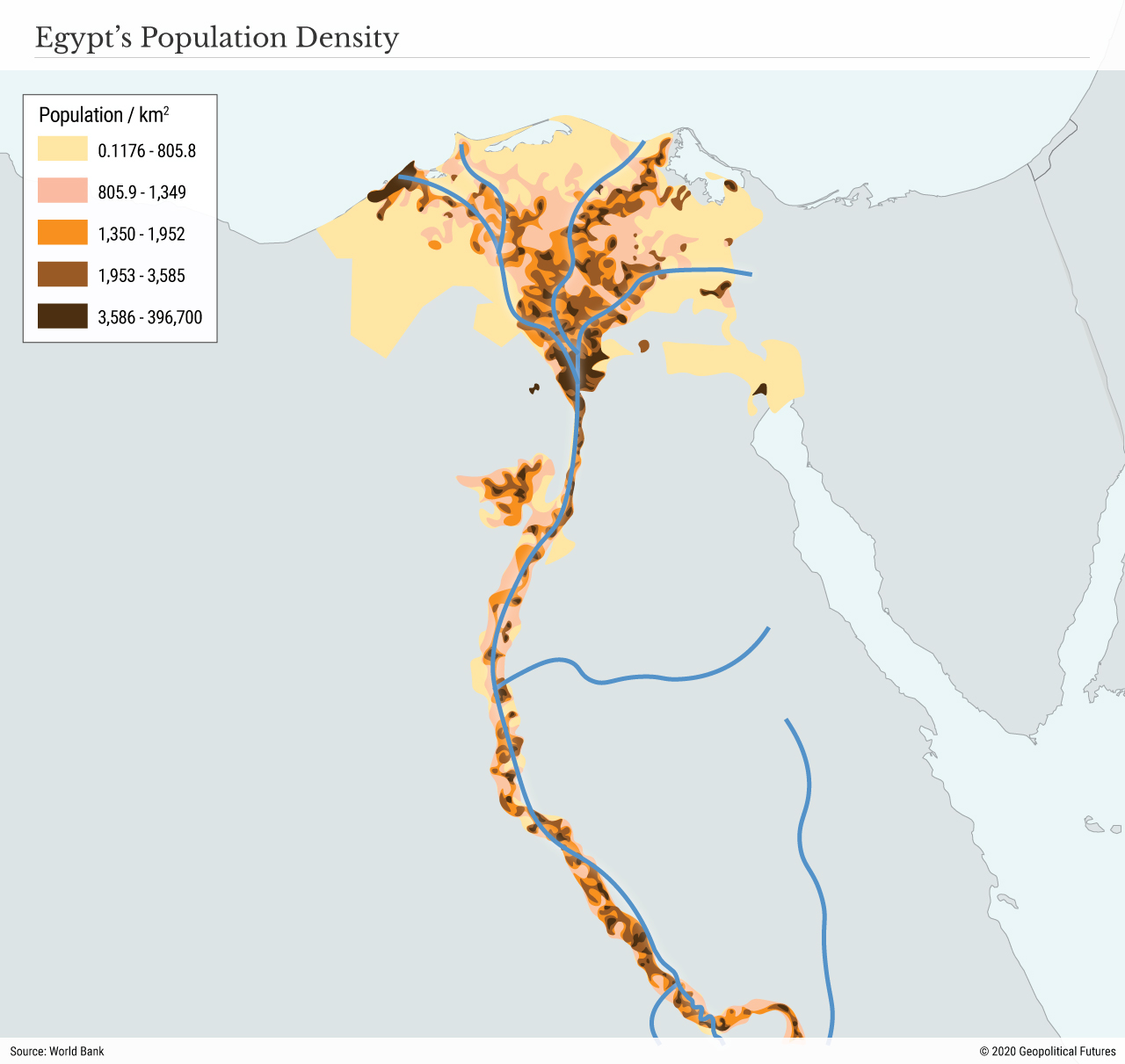

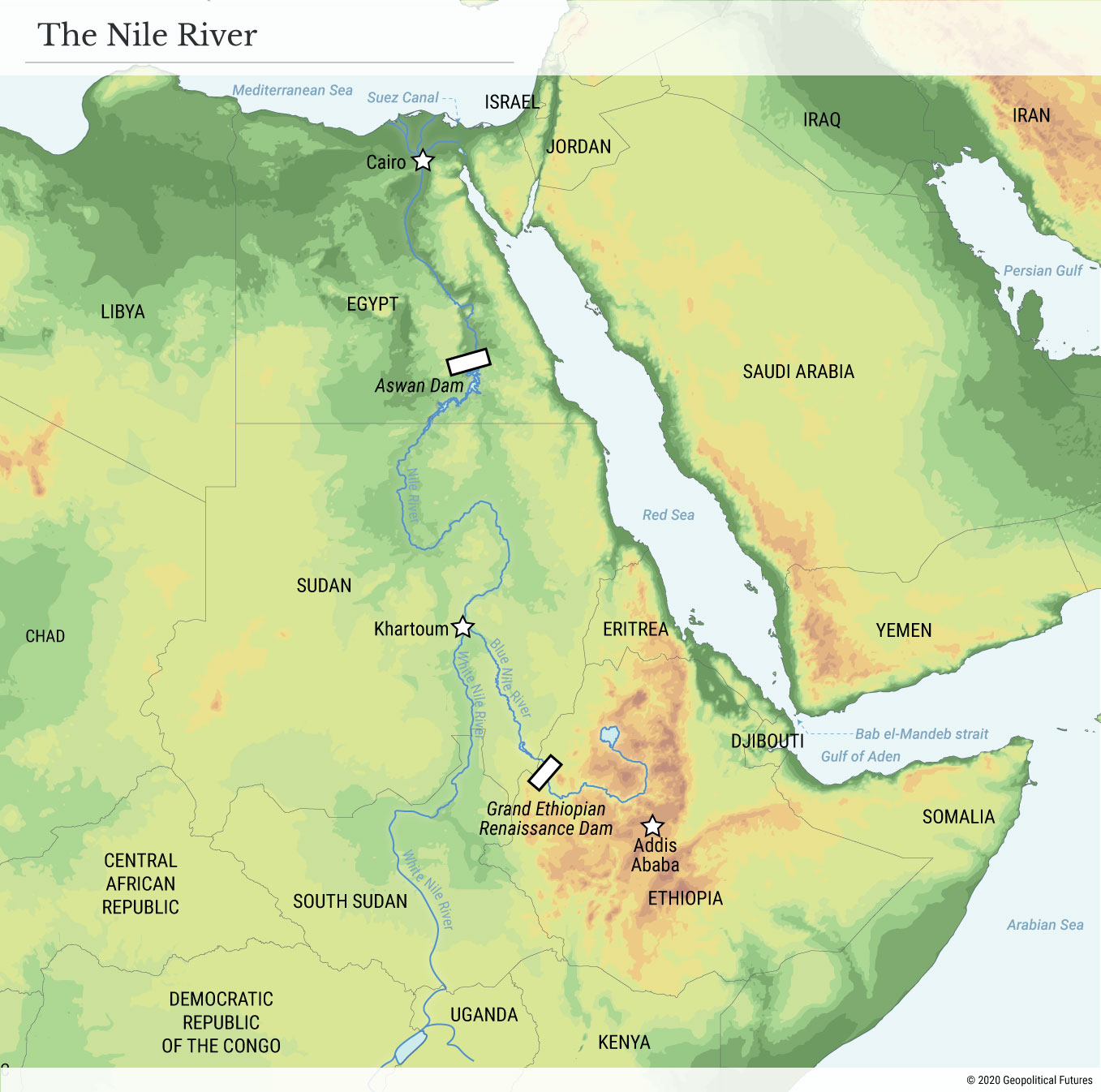

Egypt has been displeased with Ethiopia’s plan to dam the Blue Nile River since the project was announced more than a decade ago. Egypt’s very existence depends on its access to the waters of the Nile, which supplies 98 percent of the nation’s water. And although the river valley and delta constitute less than 5 percent of Egypt’s land area, they are home to 95 percent of its population. Despite Cairo’s objections, work on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam continued. It was finished in 2023 and has been producing electricity for more than 12 months.

But the conflict does not end there. Addis Ababa’s other recent foreign policy maneuvers have caused alarm. The most significant of these is Ethiopia’s outreach to Somaliland, a breakaway region in neighboring Somalia, and their conclusion of an agreement granting the Ethiopian navy access to one of the separatist region’s ports. The Somali government’s outrage over the deal created an opportunity for Egypt to start forming a coalition to resist Ethiopia’s growing influence in and around the Horn of Africa. However, Somalia’s emergence as a proxy battleground also threatens to draw in other countries from the Middle East and beyond with their own interests to protect.Water Wars

Diplomacy among the Nile riparian states has failed to alleviate Cairo’s worries. Six of the eight Nile states – all of them upstream of the GERD – endorsed the Cooperative Framework Agreement setting out usage rights for both the Blue and White Nile. Egypt and Sudan rejected it, instead insisting on the continuation of a 1959 agreement that granted all water rights to Egypt and Sudan along a 75-25 split, with no allowances for the upstream states. But Sudan was not much of an ally. It had not raised objections to the dam until Ethiopia began filling its reservoir in 2020, causing a sudden drop in water flow to Sudan and creating problems for its pumping stations. Even then, Sudan has been in a state of civil war for 18 months, rendering it incapable of lending meaningful assistance to Egypt in the struggle for its water rights.

Despite the objections of Cairo and Khartoum, the CFA took effect on Oct. 13. So far, Egypt has suffered no major disruptions to its water supply as a result of the GERD. However, Ethiopia has not guaranteed a specific volume of water to Egypt, exacerbating Cairo’s fears that during times of drought Addis Ababa could restrict the supply, endangering Egypt’s food production in the process.Just as Egypt seemed to be at its most powerless, the crisis in Somalia threw it a lifeline. For a long time, Ethiopia was a critical provider of security in Somalia, but since its January 2024 agreement with Somaliland for port access, Mogadishu has considered Addis Ababa a hostile foreign power. From Somalia’s perspective, Somaliland lacks the authority to strike such an agreement with a foreign government, and Ethiopia’s decision to proceed anyway directly undermines Mogadishu by effectively (if not officially) recognizing Somaliland’s sovereignty.

Why did Ethiopia disregard Somalia’s predictable objections and sign the agreement anyway? Because secure and stable access to the sea is vital to every nation’s trade, including its supply of food and other necessities, and landlocked countries such as Ethiopia do not get to choose their access points independently. Moreover, Ethiopia sees itself as a regional power, and it is difficult to have influence in and around the Red Sea without a naval force present.

However, not everyone is ready to welcome a more influential Ethiopia. Egypt, for one, sees Ethiopia’s rise as a potential challenge to the status quo around the Suez Canal, whose transit fees are a critical source of revenue for Cairo. Those revenues have already nosedived as Iranian proxies in Yemen have attacked commercial vessels in the Red Sea to punish Israel and its supporters, and Israel’s war against Gaza is happening right on Egypt’s doorstep.

Opportunities in Somalia

An opportunity for Egypt to push back against Ethiopia is finally emerging now that the African Union’s transitional peacekeeping mission in Somalia is winding down. Although the mission’s mandate will conclude at the end of the year, Mogadishu anticipates it will continue needing foreign security assistance in its fight against the al-Shabab militant group. However, because of the dispute surrounding the Somaliland deal, Somalia does not want Ethiopia – including the more than 10,000 Ethiopian soldiers already in the country – to be part of this future presence.

Ethiopia has so far refused to cooperate with Somalia’s request for it to withdraw its troops, but that has not stopped Egypt from leaping at the chance to fill the impending void. A thousand Egyptian commandos have already been deployed to Somalia, and more than 10,000 additional troops are scheduled to arrive by January to assist in the fight against al-Shabab. In addition, Somalia has started deploying army units accompanied by Egyptian military advisers to the areas of the country that form Ethiopia’s supply lines, likely to hinder any attempt by Addis Ababa to send reinforcements.

In July, Egypt signed a defense deal with Somalia promising to assist it with arms, training and troop deployment. The following month, two Egyptian C-130 cargo planes loaded with arms and ammunition landed in the Somali capital. It was the first shipment of its kind in more than 40 years. Another delivery of military equipment arrived by ship in September and included more small arms and ammunition as well as anti-aircraft guns and artillery. On Nov. 3, an Egyptian cargo ship delivered a third batch of weapons, this time more modern than before.

For Ethiopia, the threat from the Egyptian deployments to Somalia is twofold. First, there is the risk that al-Shabab could regroup and attack Ethiopia’s eastern provinces from its strongholds near the border. This was a key reason Addis Ababa was willing to send tens of thousands of troops next door in the first place, and Egyptian troops are unlikely to dedicate as much time and effort to rooting out jihadists in the border region. Egypt is more likely to prioritize security in regions from which al-Shabab could threaten the shipping corridors in the Red Sea and access to the Suez Canal.

The second risk is that Egyptian forces deployed in Somalia could attack Ethiopia directly. Cairo has cautioned its citizens to leave Somaliland in anticipation of a potential conflict. But a direct clash is unlikely. Secure ship traffic in the Red Sea is more important to Egypt, and other interested countries – such as Kenya, which wants Ethiopia to continue to play a role in the security mission in Somalia – would oppose an escalation of the standoff.

Regional and International Stakeholders

In October, Egypt and Somalia’s coalition against Ethiopian aggrandizement added Eritrea to its ranks. Once part of Ethiopia, Eritrea fought an almost 30-year war for independence that ended in victory in 1991. From 2020 to 2022, the fight against Tigrayan nationalist paramilitaries in northern Ethiopia, close to Eritrea, brought the two countries briefly together, but Addis Ababa inked a peace agreement with the Tigrayans in late 2022 that has not stopped Eritrean forces. Additionally, when Ethiopian ministers and the prime minister started talking in 2023 about the existential risks associated with being landlocked – a situation created by Eritrea’s secession – Eritrea interpreted it as a threat. Before the Somaliland agreement, it looked as though Ethiopia and Eritrea might even go to war with each other. Consequently, Eritrea was pleased to host the presidents of Egypt and Somalia on Oct. 10 in its capital, where they cemented their deepening security ties.

Other countries in the region have taken note of the escalating dispute and started to make their own moves. A direct conflict between Egypt and Ethiopia is highly unlikely considering Egypt’s preoccupation with its northeastern border and Red Sea shipping and Ethiopia’s domestic security issues. However, there is a risk that the two could turn Somalia into a proxy battleground. Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia all have significant interests in Somalia and want to avoid a larger conflict around the Horn of Africa.

Turkey, which signed a military pact with Somalia in January, views the escalating conflict as a direct threat to its offshore oil and gas interests. Turkey has deployed naval vessels to help protect Somali territorial waters and offshore drilling ships to advance exploration. It also maintains a robust presence across Somalia, investing in schools, training Somali armed forces and police, and strengthening trade. But Turkey’s efforts to mediate between Somalia and Ethiopia over Somaliland – and now with Egypt – have so far failed.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE also have significant stakes in Somalia and Somaliland, especially in port infrastructure. The UAE’s DP World operates the Berbera port, holding a 51 percent share, with Somaliland holding 30 percent and Ethiopia 19 percent. Until Turkey’s recent military engagement, the UAE also funded part of the Somali army’s salaries and provided training. But while both Gulf countries oppose conflict in Somalia, their focus remains diverted by the situation in Israel, limiting their willingness to intervene directly.

The risk of a regional conflict playing out in Somalia is still quite remote. However, the tensions between Somalia and Ethiopia presented an opportunity for Cairo to gain leverage in its own disputes with Addis Ababa. With the Middle Eastern stakeholders preoccupied, it is possible that Egypt will see this as an opportune time to pressure Ethiopia into concessions over the GERD and Nile water supply issues. Both countries believe their national security is tied to water; for Egypt it’s the Nile, and for Ethiopia it’s the Red Sea. As more Egyptian troops arrive in Somalia, and if Ethiopia decides it needs to maintain its troop presence in the country, escalation is likely. Similarly, Ethiopia’s unwillingness to reconsider its port deal with Somaliland ensures that Somalia will remain a hostile neighbor.

BLOG

Egypt and Ethiopia’s Dispute Is Getting Worse

November 8th, 2024

November 8th, 2024

Via Geopolitical Futures, a look at what started as a disagreement over water rights threatens to develop into a proxy war in Somalia.

This entry was posted on

Friday, November 8th, 2024 at

3:46 am and is filed under

Egypt, Ethiopia, Nile, Somalia. You can follow any responses to this entry through the

RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

© 2025 Water Politics LLC . 'Water Politics', 'Water. Politics. Life', and 'Defining the Geopolitics of a Thirsty World' are service marks of Water Politics LLC.