BLOG

November 11th, 2015

Courtesy of China Water Risk, a detailed look at Asia’s vanishing glaciers & shares concerns over the region’s water future:

Highlights

- The Hindu-Kush Himalayas covers 8 countries & is the source of 10 major rivers which feed 17 countries in Asia

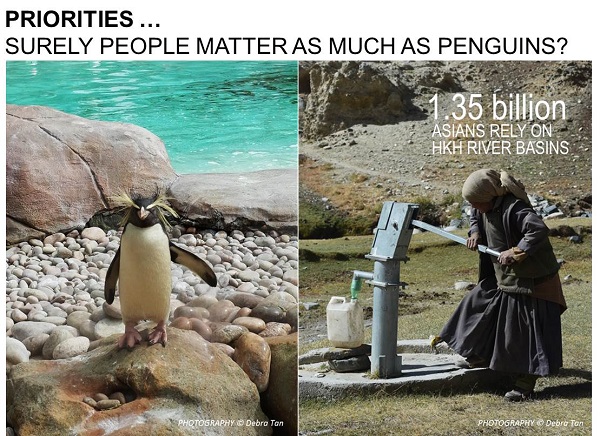

- 1.35bn Asians rely on these river basins as do major cities; yet media focus on Antartica led me to worry over penguins

- Real risks & threats need to be redefined & reassessed: Asians need to take urgent ownership of their water future

Despite the increased focus on water in the world view, precious little attention is paid to the great Himalayan glaciers which form the headwaters of some of the planet’s most vital waterways that affect 1.35 billion people. Obsessed with the rapid decline of these ancient temples of ice, award winning explorer Jeff Fuchs and China Water Risk’s Debra Tan undertook a month-long quest to live upon two of the India Himalayas’ great stalwarts of ice – the Bara Shigri and the Lasermo Glacier. Their journey allowed them to collect local tales and witness first-hand the urgency of the Himalayas’ water and ice issues.

Below, Tan recounts her thoughts on the journey and shares why a more complete view of the Himalayan paradigm is seriously needed while Fuchs’ reflections on Bara Shigri’s retreat can be read here. A more day-to-day account of the entire journey can be found here.

Out of sight and out of mind. This is the persistent nagging thought that interrupts my “moment”. I am on a glacier at 4,500m in the Himalayas trying to achieve a zen-point but instead, I am having a mild panic attack. I find myself out of breath sitting down. Admittedly, breathlessness can blamed on the altitude but really it was the reality of the sheer magnitude of the problem that was causing me to panic.

I agreed to help build China Water Risk because I was worried about glacial melt in the Himalayas. Back in 2010, I was appalled that I was more worried about the penguins in Antarctica than the 1.35 billion Asians who relied on the meltwaters from the “Third Pole”. Not that I no longer care for penguins but why were the 1.35 billion people who rely on these 10 river basins in my blindspot? Was it because they were out of sight and out of mind?

“Back in 2010, I was appalled that I was more worried about the penguins…”

So I turned to “Uncle Google” where I found lots of scientific journals, publications and expert views on the topic. I thought of myself as quite well read but clearly I wasn’t. How could I have missed this? The Third Pole or the Hindu-Kush Himalayan region (HKH) is the source of 10 of Asia’s major rivers.

This is water we are talking about: 2% short and we feel thirsty; 15% short and we die. We know we cannot live without it, yet we adopt a cavalier attitude and assume that our freshwater resources are forever available. It could not be clearer, but yet somehow it hovered in my blindspot. I realized then that working on alleviating poverty and improving healthcare and education were not enough when “the house” is falling apart. And so my own journey into water began with China Water Risk.

Five years on, I am standing on Bara Shigri, one of the longest glaciers in Himalayas, awed and depressed all at the same time. It is easy being awed – the space dwarfs me, the sounds of glacial melt and shifting moraine encompasses. It never stops – even at night when the glacial streams freeze; avalanches of rock fall take over as ice expands in the rock fissures. There are no “control” avalanches here – I spent a few nail-biting nights lying awake listening to rocks rolling amid the patter of hail and snow on my tent.

“…working on alleviating poverty and improving healthcare and education were not enough when “the house” is falling apart.”

“You must focus, you could break your leg with every step and it take days for us to carry you out” warns Jeff (my partner-in-crime in this adventure) before we start our ascent. Yes, I have totally wandered out of my comfort zone. So being in the company of Jeff (one of Canada’s Top 100 explorers), excellent mountain guides Purun & Kamal, veritable sage, Karma was reassuring … and then there was Norbu the horseman and an ‘army’ of ridiculously strong porters.

Although they had mentally walked me through the day, we were caught off guard by drastic change in terrain caused by the perpetually melting ice. Bara Shigri which translates as the “Great Glacier” is undergoing great change – I won’t go into this as Jeff describes the retreating pains of this glacier so beautifully here.

But “caught off guard” is another one of those nagging thoughts to add to “blindspot” and “out of sight, out of mind”. This is why I worry …

“Out of sight, out of mind”

Of course it is out of sight – I had to take a plane, train, drive, camp and trek just to get there. So the “what has it got to do with me” attitude prevails – lake bursts in the high mountains which wipe out villages do not affect the urban lifestyle. Besides, many believe “it is not my problem – the governments in those countries are responsible”.

But surely it is our problem. The 10 rivers that flow from the HKH feed some of Asia’s major cities: Shanghai, Kolkata, Karachi, Dhaka, Ho Chi Minh, Phnom Penh and Yangon to name a few.

Eight countries make up the HKH – China, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh but a further nine countries rely on these rivers. The Amu Darya River drains into the Aral Sea which feeds Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan whilst the Mekong River is essential to Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. In short, these rivers are key to the regional stability and economic prosperity of 17 countries across Asia.

“Blindspot”

Sea-level rise and flood risk in coastal cities – especially the 15 major cities in Asia at risk are hot topics in the climate change resilience conversation. But there is little spotlight on the fact that some of these cities face a double whammy – they lie at the deltas of these mighty HKH rivers. Many of these rivers are reliant on glacial melt – like 45% of the Indus’ flow and close to 20% of the Yangtze’s – yet how many of us are even thinking about it; let alone doing something about it?

Some Asian cities face a double whammy of sea-level rise and glacial melt

We know the governments of most of these HKH countries have many pressing issues to focus on. Mitigating climate change and protecting these watersheds may not be on top of their list. Also many simply cannot afford it.

Catalytic philanthropy can fill this gap. But are leading philanthropists focused on this? The Coutts Million Dollar Donors Report 2014 documenting grants over USD1 million from the US, UK, Russia, Middle East, China, HK & Singapore put total million-dollar grant-making at USD26.3 billion. China, HK and Singapore contributed a 16% share at USD4.3 billion – not bad. But when it came to the environment, total grants of over a million from the seven regions amounted to a mere USD170 million – less than 0.7%. HK, China & Singaporean philanthropists’ efforts amounted to a shameful USD3 million.

Everyone is more focused on another water spat in the South China Sea and COP is more focused on CO2 than H20

Basically climate change and extreme weather’s impact on water flows are in everyone’s blindspots – media attention is turned elsewhere – at another water spat – the fight over rocky outcrops in the South China Sea. Let’s face it, even at the COP negotiations dedicated to mitigating and adapting to climate change, water gets little air time.

What happens when these glaciers are gone?

“Caught off guard”

Glacial melt in the Himalayas is not pretty – it is not pristine glacial ice melting into ice floes – it’s an ugly jumble of rocks and grey ice walls. With little attention by Asian / global business leaders, the chances of being caught off guard is high – the implications of this are clearly even uglier.

Already some of these 17 countries (including India & China) are faced with limited per capita water resources. This, against a backdrop of climate change and the constraints of staying within +2oC means that Asia has fewer choices in how they develop. Old economic models based on plentiful water may no longer apply.

If the 17 countries follow the “business-as-usual” approach to development, they will end up using more water and requiring more electricity to power industry and rapid urbanisation. Adding the wrong type of power has long term implications for water but coal is cheap at the moment and hydro is tricky on transboundary rivers; wind and solar still require subsidies. Europe took a century to negotiate their river sharing agreements. Asia has less time; Nepal has already seen +1.8°C between 1975 and 2006 and the current 146 pledges get us to +2.7°C by 2100.

A river-runs-dry scenario – too far-fetched? The course of rivers change naturally but there are added stresses from excessive water use. The Yellow River is a clear example – in 1997, 90% of the lower reaches of the river had no water for 226 days – more on changing course of the Yellow River here. The Aral Sea has also shrunk – excessive water use in irrigation devastated the Aral Sea – 60% of this inland lake disappeared between 1973-2000.

Despite the gravity, how many Asian entrepreneurs / think-tanks are focused on looking for real “business unusual” models? How many universities are teaching a 360 degree view of the real threat we face? Instead, many are looking to capitalize on the growing middle class seizing the chance to sell them more and more thirsty and dirty products. And it is not just Asia, everyone else in the world are contributing to the vanishing ice. This is the scale of our problem.

We are all contributing to the vanishing ice

The course of our future is shifting

Nepal is already at +1.8°C

As I worry, the meltwaters are eroding the ice/glacier moraine beneath my feet. The course of our future is shifting. China and India, covering 62% of the HKH region are well positioned to do something. We need disruptive philanthropy, businesses, ideas and innovations in finance to fund this. We need to start redefining risk and face the real threats.

It is imperative to start now; not haphazardly but cohesively – to stop squabbling over “small matters” and to keep our eye on the prize – these arterial rivers are the lifeblood of Asia and the HKH the heart that pumps it. It is time we dealt with the cholestoral of climate change, bad damming practices, river diversions, built in product obsolescence, the impact of never-ending consumption, throwaway fast fashion, unnecessary packaging, explosive bottling of glacial water and illegal mining.

Today’s business, investment and consumption decisions matter in securing the future of our common waters. We can start with a perspective change on how we look at our mountains – not as something to conquer but to preserve at all costs.