BLOG

December 16th, 2023

Courtesy of The New York Times, a report on California which – as the world warms – is re-examining claims to its water that have gone unchallenged for generations:

The story of California’s water wars begins, as so many stories do in the Golden State, with gold.

The prospectors who raced westward after 1848 scoured fortunes out of mountainsides using water whisked, manically and in giant quantities, out of rivers. To impose some order on the chaos, the newcomers embedded in the state’s emerging water laws a cherished frontier principle: first come first served. The only requirement for holding on to this privileged status was to keep putting the water to work. In short, use it or lose it.

Their water rights assured, the settlers gobbled up land, laid down dams, ditches, communities. Shrewd barons turned huge estates into jackpots of grain, cattle, vegetables and citrus. California grew and grew and grew, sprouting new engines of wealth along the way: oil, Hollywood, Apple, A.I.

Yet, still today the state is at the mercy of claims to water that were staked more than a century ago, in that cooler, less crowded world. As drought and overuse sap the state’s streams and aquifers, California finds itself haunted by promises, made to generations of farmers and ranchers, of priority access to the West’s most precious resource, with scant oversight, essentially forever.

For many beloved products — nuts and grapes, milk and lettuce — America depends heavily on California. Its farms produce billions of dollars more each year than those in Texas, Nebraska and other states far more defined by agriculture. Water sustains jobs and livelihoods across the state’s economy, which outranks those of all but a handful of nations. Yet in no state does rainfall vary more each year, swinging between deluge and drought in a cycle that global warming is intensifying at both ends.

With so many people, plants and animals competing for this fickle bounty, water fights have shaped California at every stage of development, all the way back to its infancy as a state, when its abundance seemed limitless and settlers took it as their duty to commandeer it. Now, Californians are being forced to confront the limitations of nature’s endowment in new and urgent ways.

And so, to address this most 21st century of crises, a state that prides itself on creating the future is first reckoning with its past.

In the Central Valley, home to some of the nation’s most productive cropland, officials are taking a hard new look at water rights that date back to the 19th century. They are asking farmers to provide historical records to back their claims and using satellite data to size up who is taking river water and how much. A Times analysis of state data identified many growers who reported their use in questionable ways.

In California’s rugged north, regulators are considering throttling supplies to cattle ranchers and other users who for decades have been siphoning too much from the streams, at times in open disregard of the law, worsening a collapse in salmon populations.

And in desert highlands of the Central Coast, the state’s efforts to stop groundwater depletion have spurred two of the world’s largest carrot growers to sue all of their neighboring landowners, big and small, so they can keep pumping.

California has been regulating river flows, however imperfectly, for more than a century. But it didn’t even begin restricting groundwater extraction in a major way until a mere decade ago. Farmers in many areas must now figure out how to stay in business by using less groundwater themselves — or by ensuring their neighbors do.

“The reality is that California had a pretty soft touch in water rights administration” compared with many Western states, said E. Joaquin Esquivel, the chair of the state’s water board, California’s main regulator. “The system worked for as long as it really could.”

Climate change is only deepening the strains on the state’s rivers, which are essential to cities and farms alike. In dry years, less snow is piling up in the mountains to feed them. And more of what does flow downriver ends up evaporating, soaking into parched topsoil or being pulled into the ground as farmers pump out the aquifers.

How California manages could have ramifications well beyond occasional curbs on watering lawns. In the San Joaquin Valley, the Central Valley’s enormous southern half, researchers estimate that more than half a million acres of farmland may need to be taken out of cultivation by 2040 to stabilize the region’s aquifers.

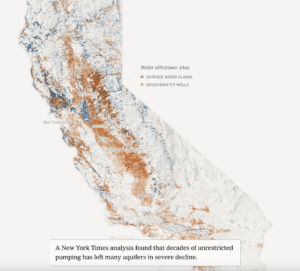

California is hardly the only place where people are reconciling with choices made generations ago about land, water and other shared resources. A Times data investigation this year found groundwater in distress nationwide and exposed a broad failure to address exploitation or even reliably track water use. Yet, few places have wrested such immense riches out of their natural inheritance as California has. New choices about how to share that inheritance might not be able to avoid cutting into one pot of riches or another.

“We can’t fix it without stepping on toes,” said David Webb, who has worked for decades to protect the Shasta River in California’s far north, one of many overworked streams statewide. Come summertime, it’s not unheard of that ranches and farms all but drain the Shasta to a trickle.

FIXING ‘USE IT OR LOSE IT’

Nowhere do the strands of California water history get tangled into trickier knots than in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the vast fertile estuary where the main rivers that nourish the Central Valley pour into the San Francisco Bay, then out to sea.

Mr. Esquivel, the water board’s chair, called the Delta “our most wicked of problems.”

The heart of it is that many of the area’s farms and irrigation districts have been drawing from the Delta’s braided channels for well over a century, before the state even had a water board. This gives them extraordinary privilege in California’s seniority-based system: When there isn’t enough water to go around, they get first dibs. And for a long time, a lot of them didn’t have to provide the state with many details about how much water they actually used.

That is starting to change. Not only is the water board demanding more information from growers on their use, but it’s also starting this year to use satellite analysis that estimates how much evaporates from their fields, a powerful check on farmers’ claims.

All of this is helping the state form a clearer picture of where water goes in the Delta.

Yet growers’ self-reported numbers still contain peculiarities, suggesting that many are probably submitting ballpark estimates rather than precise measurements. The Times analyzed state data from 2010 to 2022 and found that monthly use reports associated with about a quarter of Delta water rights contained a significant share of duplicates — identical numbers, over and over, for months. Sometimes years.

Another issue: Many Delta growers claim not just one water right, but several. California’s use-it-or-lose-it system provides an incentive for them to report using more water than they actually do, or even to count the same use under more than one claimed water right.

Faulty or misleading data can have far-reaching consequences during drought. If lots of growers are double-counting their use, then officials may think less water is available for everybody else than there actually is.

David Weisenberger, the general manager of the Banta-Carbona Irrigation District, which claims rights on the San Joaquin River that date back to 1911, said he double-reported the district’s use for years to avoid losing its water rights.

Recently, he began providing more accurate accounting after the water board’s lawyers assured him that he wouldn’t be forfeiting the district’s rights by doing so. But part of him still worries about future cuts.

“Who knows what they’ll do?” he said on a recent bright morning, driving past neat rows of grapes in his district’s patch of the Delta.

Mr. Weisenberger’s father grew beans and grain in the Central Valley. His grandfather raised cattle. Water disputes used to be handled locally, he said. If someone didn’t think they were getting their rightful share, they would go talk to whoever might be taking too much upriver. Maybe they’d sue.

Neighbors held neighbors accountable, Mr. Weisenberger said, so state officials had no need to know how much water everybody was taking. Today, though, “they’re headed in the direction of ‘God squad’ — they know better than anybody,” he said.

Already in California’s most recent droughts, the board has used new data and analysis techniques to justify deploying aggressive emergency orders to stop thousands of growers in the Delta watershed from taking water. “Emergency regulations don’t leave any room for due process,” Ed Zuckerman, a third-generation Delta farmer, said. “We will fight it to our last breath.”

So far, though, it isn’t the Delta where the board’s efforts have prompted the fiercest complaints. Or the most blatant defiance.

THE BATTLE OF CATTLE AND SALMON

Follow the Sacramento River 200 miles upstream, past its headwaters in the shadow of Mount Shasta, and you start to feel about as far from California’s coastal centers of influence as you would on Mars.

Morning mists hover in the pine-perfumed air. Cattle graze on lush mountain meadows. This is a proudly independent-minded corner of the state, with an on-again, off-again history of trying to secede from it.

It’s here that the water board this year began contemplating a quietly explosive policy: To protect the imperiled salmon that spawn in the Scott and Shasta Rivers, it is considering permanently limiting ranchers’ access to the streams, effectively circumscribing their long-established water rights. The board has done this in both rivers during California’s latest droughts. Now it might restrict their use for good, drought or no drought.

For decades, ranches and farms have been slurping the Shasta and Scott down to small fractions of their natural flows in dry years. Migrations of Chinook and coho salmon have plummeted, harming the Native American communities whose diet and culture center on the fish.

The problem received a burst of fresh attention in the severely dry summer of 2022, when some ranchers in the Shasta Valley flouted state orders to limit water use. To save their herds, they turned on their pumps. The river’s flows quickly dropped by more than half.

For eight days, this continued. And the water board was powerless to do anything but impose its largest possible punishment: a fine of $500 per day of illegal diversion, split between the 80 or so scofflaws. In other words, $50 each, a paltry price to pay.

In response, state lawmakers have put forth a bill that would increase penalties to $10,000 a day.

Mr. Esquivel, the water board’s chair, called stronger salmon protections “long overdue.” When it comes to the state’s treatment of the Karuk, Yurok and other tribes, “there’s a history that has to be acknowledged,” he said.

Economic development has transformed California’s northernmost landscapes in great waves. Fur trappers decimated the beavers. Loggers sawed through old-growth forests. Miners dredged the Scott River in pursuit of gold, creating a 600-acre gravel moonscape that remains to this day.

All throughout, salmon have paid a price. In the 1930s, as many as 82,000 Chinook migrated up the Shasta each fall. Last year, only 4,500 made the trip.

“Our religion was salmon,” said Kenneth Brink, the vice chair of the Karuk tribal council. “When the salmon went away, the people went away, the ceremonies went away.”

Ranchers, for their part, see a parallel threat in water restrictions. One directed at their way of life, rather than the tribes’.

Leaving so much water in the rivers would mean “immediate lights out” for agriculture, said Theodora Johnson, who raises cattle in the Scott Valley. “My kids are seventh generation here,” she said. “I have to do everything I can to try to save it.”

ANTIQUATED, UNSEARCHABLE RECORDS

To understand one reason California struggles so mightily to track its water, you might visit a small room in Sacramento that is jam-packed with some of the state’s most valuable mysteries.

There are documents written in the ornate cursive of bygone times. Corduroy-bound ledgers. Maps whose labels have come unglued. Sepia photos of charmingly unphotogenic subjects: dirt fields, pear orchards, wooden sluices.

These are the water board’s records of every water right it has handed out since the early 20th century. Millions of musty files, smelling of history. And they are unwieldy, unsearchable — a mess.

Starting next month, all of this forgotten paper will, for the first time, be scanned and made accessible online to help resolve water disputes and better parcel out supplies during droughts. But soon, the board could go even further, demanding more information from farmers who hold the state’s oldest water claims, those dating back to the pioneer era.

In October, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law giving the board express authority to investigate whether these users have valid rights and, if so, are using them appropriately — a prospect that has rankled farmers up and down the state.

In the Central Valley, “you’ve got so many water-rights holders who believe their water rights are whatever their granddaddy said they were,” said Felicia Marcus, a visiting fellow at Stanford and former chair of the water board.

At the moment, the board’s records on California’s senior-most water users are sparse. Deeds, maps and notices might well exist that would tell regulators more about the origins of longstanding claims. But many of those documents have spent the past century or more hidden away in libraries and courthouses, or locked up at farms and irrigation districts.

The water board is hoping to bring more of them out of the shadows.

No other state has “this arbitrary thing that says that you can’t even ask basic questions about the validity of a right” just because it’s old, said State Senator Ben Allen, who proposed the bill that the governor recently signed.

The water board will “start small” with its new powers, said Erik Ekdahl, its deputy director in charge of water rights. It will first ask growers to update records and data here or there. As Mr. Ekdahl put it, the board might ask things like: “Hey, can you go in and update your place-of-use map? Because right now the one we have is literally a bunch of 3-by-5 pictures that you’ve taken and drawn on with a Sharpie, and we can’t actually make heads or tails of it.”

Eventually, though, the board might start digging deeper. And that has farmers on edge.

That’s because files that might help validate someone’s 19th-century water claim might already be lost to time, said John Herrick, a lawyer who represents growers in the Delta. “You have to find somebody’s journal that said, ‘I got up today on Aug. 21 in 1890 and opened the sluice gate,’” he said. “Jesus! That doesn’t exist.”

BABY CARROTS, BIG CONFLICT

In a sun-scorched pocket of desert between the Sierra Madre Mountains and the Caliente Range, there is a length of Highway 166 flanked each summer by rows of lacy, bright-green stalks. These are the carrots of the Cuyama Valley, many destined to be clipped and shaved into those quintessential emblems of American supermarket ingenuity: baby carrots.

Of late, these carrots have become an emblem of something else, too: the state’s painful groundwater crisis.

About a decade ago — and, arguably, decades too late — California legislators finally did something about the fact that many of the state’s vital aquifers were being pumped dry beneath their feet. They passed a law, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, to end overuse and depletion.

Seen one way, the law is remarkably optimistic. Its premise is that neighbors will be neighborly: Instead of issuing top-down orders on how to conserve, the law leaves it up to local groups to work it out among themselves.

But in retrospect, this may have overestimated Californians’ neighborliness when water is at stake.

In Cuyama, the corporate owners of the carrot fields are suing every other landowner in the valley: farms, vineyards, ranches, even the tiny school district. Their aim, effectively, is to make their neighbors share more of the burden of reducing water use under Cuyama’s sustainability plan. The case goes to trial next month.

“They know that their water table has gone down,” said Jim Wegis, who grows olives and pistachios nearby and is a defendant in the case. “It keeps going down. And they want us to help support their habit.”

Daniel T. Clifford, the general counsel for Bolthouse Properties, one of the plaintiffs, said the valley’s groundwater plan had left the companies no choice but to sue. The plan calls for total pumping to be cut by half to two-thirds over the next 15 years. So far, though, it is imposing those cuts only in the area of the valley that is dominated by Bolthouse and the other carrot giant, Grimmway.

“That’s not fair or consistent with California water law,” said Robert G. Kuhs, a lawyer representing the other plaintiffs, the owners of the land that Grimmway farms. “We strive to be good neighbors.”

In their section of the valley, the two carrot growers have used more water in recent decades than everyone else combined. Groundwater levels there are projected to fall by as much as seven feet a year, compared with two feet or less in other areas.

Others in Cuyama suspect that the carrot companies are trying to make as much money as they can in the valley before water restrictions make growing unviable and they move their operations someplace else.

Mr. Clifford, the Bolthouse Properties lawyer, said the carrot growers would always need to farm in Cuyama. The reason, he said, is all of us, the carrot-eating public.

“The American consumer has grown to absolutely rely” on being able to buy carrots 365 days a year, Mr. Clifford said. The high elevation of the Cuyama Valley makes it possible to produce them when it’s too hot to do so elsewhere. “They want that carrot year-round,” he said.

On this at least, he and Mr. Wegis, one of the neighboring growers his company is suing, can agree. Except that Mr. Wegis sees it as part of the problem.

“We as farmers have spoiled the public,” Mr. Wegis said. “Everybody’s used to going into the store and seeing everything they want, all the time.”