BLOG

November 18th, 2023

Via Water Education Foundation, a report on the growing influence of First Nations as the Colorado River shrinks:

The climate-driven shrinking of the Colorado River is expanding the influence of Native American tribes over how the river’s flows are divided among cities, farms and reservations across the Southwest.

The tribes are seeing the value of their largely unused river water entitlements rise as the Colorado dwindles, and they are gaining seats they’ve never had at the water bargaining table as government agencies try to redress a legacy of exclusion.

The power shift comes as the federal government and seven states negotiate the next set of rules governing the river that flows to nearly 40 million people and irrigates more than 4 million acres of farmland.

The tribes stand to hold outsized sway in those discussions. Altogether, they hold rights to more water than some of the states in the Colorado River Basin, which stretches from Wyoming to Mexico. Tribes such as the Navajo Nation, Gila River Indian Community and Jicarilla Apache Nation also hold some of the most senior rights to the water, giving them first dibs on the precious flows before cities like Phoenix and Los Angeles.

“Our tribe plans to fully develop our water to support our economic development and the resiliency of our people.”

~Lorelei Cloud, vice chair of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe

But most tribes haven’t been using their full allotment because they lack the infrastructure to put their water to use or because their water rights remain unsettled.

Large volumes of water meant for the tribes flow downstream and are captured, stored and used by cities and farms that have far more developed networks of canals, pumps, reservoirs and water treatment plants. The water not used by tribes has helped to slow the decline of major reservoirs like Lake Powell and Lake Mead and spur growth in the arid Southwest.

Now, tribes are poised to use more of their water, straining an already oversubscribed river system that has been pushed to its limit by more than 20 years of sustained drought.

While some water users in Arizona, Nevada and Mexico are facing a third straight year of water cuts, tribes with ironclad water rights are reaping record amounts of federal infrastructure funding under the Biden administration.

“Downstream users have built a reliance on tribes and their unused or unsettled water,” said Lorelei Cloud, vice chair of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe in southwest Colorado. “But our tribe plans to fully develop our water to support our economic development and the resiliency of our people.”

Once an afterthought, Basin tribes are gaining recognition and bargaining power. In the past five years, the tribes have seen significant advances:

- Thirsty water users in states like Arizona and New Mexico are leasing water from tribes or paying them to leave water in the system.

- The federal government began engaging directly with tribes alongside state representatives on the river’s future operating rules.

- Some Basin states for the first time appointed tribal leaders to important negotiating posts.

“Tribes are very cognizant that [their unused water] is being used by others,” said Anne Castle, the federal appointee to the Upper Colorado River Commission and former assistant Interior Department secretary for water and science. “Political will has been shifting toward greater recognition of the need to address these inequities and to ensure that tribal rights and interests are protected in these ongoing discussions that are going to result in changes to the way the Colorado River operates.”

A Major Power Shift

For over a century, compacts, treaties, laws and drought plans were hatched among the federal government, Mexico and the seven Western states that use the river: Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California.

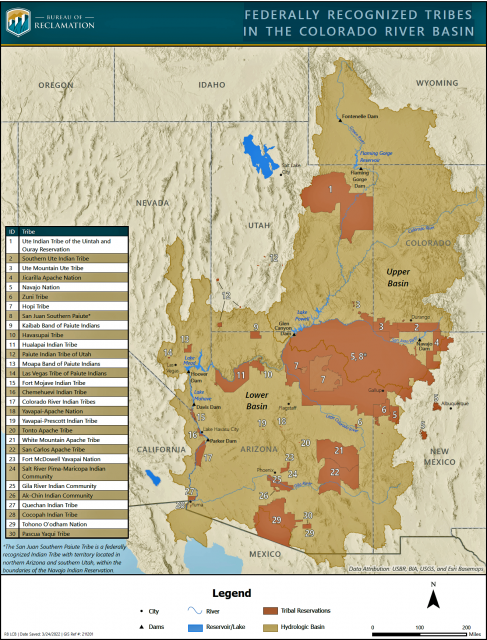

Missing from the decision-making tables were Basin tribes that hold rights to nearly a quarter of the river’s water.

In recent years, however, tribes have increasingly inserted themselves into broad discussions over the river’s management through a series of groundbreaking studies and water-sharing deals with Basin states.

The power shift can be traced back to at least 2018 when the Interior Department’s Bureau of Reclamation and a tribal consortium known as the Ten Tribes Partnership issued a study that for the first time tried to quantify the Basin tribes’ current and likely future water uses.

A 2021 update by the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy and the Environment at the University of Colorado Boulder, found that tribes hold rights to 3.2 million-acre feet or approximately 22 to 26 percent of the Basin’s average annual water supply. It also estimated the yet-to-be-settled amount of tribal water claims at 400,000 acre-feet. That’s more than the entire state of Nevada is allotted in a year.

The quantification made the enormity of the tribes’ water shares explicit and strengthened their bargaining power as the Lower Basin states and federal government were scrambling to devise a new system of water cuts. Guidelines for operating Lake Powell and Lake Mead were proving insufficient and the Basin states were locked in tense negotiations over new drought rules.

Discussions were particularly thorny for Arizona because, unlike California and Nevada, much of its allotted river water is reserved for tribes with land in the state. Under pressure to take significant water cuts, the state pitched a proposal that the Gila River Indian Community said could reduce the amount of water set aside for the tribe.

After the tribe threatened to sue, Arizona negotiated a deal to pay the tribe $60 million in exchange for 500,000 acre-feet of water through 2026. The state also paid the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) to leave some of its water in Lake Mead.

The Gila River Indian Community really forced itself into that [negotiation] process,” said Jason Hauter, a water attorney and tribal member. “It ended up taking a leadership role because it had the most water at stake.”

The 2019 deal marked a turning point: The federal government and states have since routinely offered to pay tribes to conserve water and sought their advice on the shrinking river’s future.

In 2021, the Gila River Indian Community and CRIT agreed to preserve up to 179,000 acre-feet of water under the deal known as the 500+ Plan, a move that cushioned the blow of water cuts to urban and agricultural users in central Arizona.

Earlier this year, the Gila River Indian Community agreed to conserve up to 40 percent of its river allocation each year through 2025 in exchange for up to $150 million from the federal government. It also received money for a new pipeline to deliver recycled wastewater across the reservation for irrigation, which will further reduce its reliance on Colorado River water.

“Time and again, the Gila River Indian Community has demonstrated its deep commitment to strengthening our water future in the face of historic drought,” Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema said in a statement.

An innovative deal is also underway in the Upper Basin, as the Jicarilla Apache Nation is leasing nearly half of its annual river share to bolster New Mexico’s water supply and increase San Juan River flows to benefit endangered fish. Previously, the tribe leased the water supply to coal-fired power plants that are now facing closure.

“It was the first time that we have seen an Upper Basin tribal nation and a state work together in this way.”

~Celene Hawkins, The Nature Conservancy’s head of Basin tribal engagement

Celene Hawkins, who heads The Nature Conservancy’s engagement with Basin tribes, said the Jicarilla-New Mexico deal could serve as a model for other multi-benefit water deals in the Upper Basin. The conservancy helped the two sovereign governments negotiate and implement the 10-year program, which released its first batch of water in June to support endangered Colorado pikeminnow and razorback sucker populations.

“It was the first time that we have seen an Upper Basin tribal nation and a state work together in this way,” said Hawkins, who advises the Water and Tribes Initiative, a group dedicated to enhancing tribal water resources. “Water leasing is a super-critical tool in the bigger toolbox that we’re going to need to handle the drought and water stress that’s hitting the Basin.”

Gaining Seats at the Table

It remains an uphill fight, but tribal nations are starting to gain ownership in the management of the Colorado River. Tribal members now hold a variety of positions at key agencies that decide river policy and for the first time are included in Basin-wide planning sessions.

“Attitudes have changed as we have progressed as a society, so generally there is more inclusion,” Hauter said.

Last year, Utah designated a tribal seat on its Colorado River negotiating board. The inaugural appointee, Paul Tsosie, an attorney and a member of the Navajo Nation, previously served as the Interior Department’s Indian Affairs head of staff.

This year, Colorado appointed Cloud of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe as the first tribal member of the Colorado Water Conservation Board. And last March, California appointed Jordan Joaquin, president of the Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe, to its Colorado River board.T

The federal government is also doing more to court tribal perspectives under Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American cabinet secretary.

The federal Bureau of Reclamation this past summer held a pair of brainstorming sessions open to all Basin tribes and states. Some participants cast the meetings as “groundbreaking” and an important show of transparency from the federal government.

“They were historical meetings,” said Crystal Tulley-Cordova, principal hydrologist with the Navajo Nation. “Tribes had the opportunity to be able to engage in ways that haven’t occurred before.”

Reclamation officials say the meetings will continue as Basin water users negotiate a replacement for Colorado River operating guidelines that expire at the end of 2026.

Hauter, the Gila River Indian Community member and Water and Tribes Initiative advisor, said tribes historically have found out about new water policies after they became final. He said Reclamation’s “Federal-Tribal-State” meetings will give tribes insight into what the governments are considering and a rare chance to present their own solutions for the over-tapped river system.

The top negotiators for California, Nevada and Arizona echoed Hauter’s point, saying they look forward to continued collaboration with Basin tribes.

“Successful management of the Colorado River will depend on the support and participation of the tribes,” they wrote in a recent letter to Reclamation.

Reclamation officials declined to be interviewed for this story but issued a statement saying the federal government “continues to value the input of the tribes and stakeholders … and will continue to host meetings with this group throughout the post-2026 process.” The agency anticipates publishing a draft of its long-term river management strategies by the end of 2024, with a final plan approved in early 2026.

Drought Forces Change

Basin states and the federal government are paying more attention than ever to tribal water use. Federal tribal reserved water rights were recognized in the 1908 landmark Winters v. United States decision, in which the Supreme Court held that when the government established reservations for tribes it implicitly reserved water rights for them.

Resolved tribal water claims are included in the Colorado River allocations for the states in which reservations are located. For example, the Gila River Indian Community’s 653,500 acre-feet comes out of Arizona’s annual river share.

The effects of climate change – longer, more severe droughts, more extreme hot spells and more variable precipitation – are placing a premium on tribal water. The annual amount of reserved water is often more than some tribes can use. Tribes are rarely paid for what they can’t or don’t use. Their unused reserves stay in the river system, enriching users downstream.

Over the past two decades, dry conditions have cut flows from the Colorado River’s main tributaries, but water use across the Basin hasn’t dropped equally. The unused tribal water helped keep a stable supply for some of the river’s largest users. The cushion, however, is vanishing as demand outstrips supply: Average flows in the Upper Basin have already dropped 20 percent over the past century and increased tribal water use seems inevitable.

Meanwhile, water cuts have become a reality in Mexico and the Lower Basin states.

“There’s a significant chunk of water that the tribes control that is not yet used and is a potential addition to the [water shortage] problem.”

~Anne Castle, federal appointee to the Upper Colorado River Basin Commission

Reclamation declared water shortages on the river for the first time in 2022 and again in 2023. Though much of the Basin recorded above-average snowfall last winter, the agency said cuts will continue next year for Arizona, Nevada and Mexico. With talks beginning on new river operating rules, there’s growing agreement among federal and state negotiators that an even more rigorous system of cuts needs to be implemented.

Castle, who chairs the interstate commission representing Utah, Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico, said Basin states are more concerned about the possibility of tribes maximizing their supply than they were in 2007 when the current set of guidelines was adopted.

“There’s a significant chunk of water that the tribes control that is not yet used and is a potential addition to the problem,” Castle said. “So, trying to get ahead of that problematic situation is part of the motivation.”

The 2018 Tribal Water Study estimated the Upper Basin tribes were using 670,000 acre-feet a year, or just 37 percent of their total reserved and settled rights. Castle said the commission is vetting those numbers with tribes and states to get a clear picture of how much more water tribes might develop in the coming years.

Infrastructure Problems Linger

For tribes, putting their Colorado River water to beneficial use remains a difficult proposition.

Those who have gone through the arduous process of settling and quantifying their water claims often lack the infrastructure for diverting water to farms, businesses and homes on rural reservations. Moreover, a range of laws and bureaucratic hurdles restrict how and where a tribe can use its water.

Basic projects, like expanding a water treatment plant or installing a new drinking water pipeline, can advance at a glacial pace, as tribes must deal with a variety of different federal agencies to get them approved. Even when funding is available, it can be difficult to launch projects as tribes often lack the resources to navigate the various regulations, fees and environmental reviews.

Lack of safe drinking water also continues to be a glaring public health issue. Nearly half of Native American households don’t have clean drinking water or basic sanitation, according to a study by the nonprofit Colorado River Basin Water & Tribes Initiative.

On the Navajo Nation reservation, which stretches across more than 17 million acres in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, approximately 30 percent of families live without tap water and rely on bottled or hauled supplies.

Cloud, who serves on the leadership team for the Water & Tribes Initiative, said her Southern Ute Indian Tribe uses only a quarter of its reserved water because of shoddy infrastructure. Most of the tribe’s farmers rely on a federally built system more than a century old with broken diversion structures, leaky canals and clogged ditches.

“The federal government says they don’t have the funding to fix their own infrastructure,” Cloud said. “We can’t use the water if the infrastructure is failing.”

The underutilized water supply gets chalked up as a missed economic opportunity. A North Carolina State University study this year found Western tribes collectively lose hundreds of millions of dollars each year due to their unused water.

The federal government is hoping a recent stream of funding will help tribes make use of their water rights.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law earmarked more than $13 billion for tribal projects such as the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project, which will provide a reliable water supply to parts of the Navajo Nation and Jicarilla Apache Nation reservations. The infrastructure funding includes $3.5 billion for drinking water and sewage systems and $2.5 billion to facilitate tribal water rights settlements.

Outstanding tribal water rights claims continue to complicate matters. Nearly a dozen of the 30 federally recognized tribes in the Basin have at least partially unsettled claims.

To tap into its reserved water, each tribe must negotiate with the state or states where it has land to quantify the size of its share. This process averages 22 years and can cost tribes millions of dollars in legal and consulting fees. There is an additional layer of federal oversight, as Congress must sign off on deals made between states and tribes.

Expediting the outstanding claims, most of which are in Arizona, is in the best interest of Basin water users as talks intensify over a new set of river guidelines, Castle said.

“It’s a burden on everybody to have this unquantified amount hanging out there,” she said.

Tribes as Part of the Solution

Tribal leaders and experts say being involved in the crafting of the next set of river management rules could benefit Basin tribes in a variety of ways, including compensation for their unused water.

Hauter, of the Gila River Indian Community, said one potential solution would involve paying tribes to not develop or increase their water use for a set period. These “forbearance” deals would suspend a portion of a tribe’s allotment and continue to allow non-tribal users to use the water.

Joaquin, president of the Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe in California, said forbearance deals like the one the tribe negotiated with California water agencies in 2005, generate income for tribes for badly needed drinking water infrastructure and reduce the risk of new draws on the river.

“This is an opportunity that should not be squandered,” Joaquin said in a recent letter to Reclamation officials.

Additional support for tribal water infrastructure may also be on the horizon. By being in the same meeting rooms, tribal leaders will be able to convey the scope of their drinking water problems to the federal government and states’ top negotiators.

“It’s a straight-up issue of equity for American citizens,” Castle said.

While the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law provided a “groundbreaking” amount of money for fixing and building new drinking water systems, Castle said tribes need additional assistance getting their projects shovel-ready. More money would help tribes with the design, engineering, permitting and other pre-construction stages.

With the demand for tribal water increasing across the Basin, tribes could press to level the playing field when it comes to profiting from their unused water.

Federal laws enacted more than a century ago, decades before any Southwest state was established, effectively bar tribes from sending water off their reservations. Marketing water to non-tribal users requires congressional approval, a difficult task to achieve for even the most well-resourced, politically connected tribe.

“We’re not going to address the declining [water supply] without thinking about the significant investments that need to be made in tribal lands.”

~Peter Culp, a Western water law and policy attorney

CRIT got the nod from Congress earlier this year to market some of its allotted Colorado River supply off-reservation. It plans to use the revenue to make its water delivery systems more efficient.

Streamlining the process would allow tribes to find new ways to share their water with farmers or cities.

The states and the federal government could also find new ways to support investment in tribal lands. Peter Culp, an attorney specializing in Western water law and policy, said tribes often do not have the means to undertake projects that could help reduce erosion, water pollution and wildfire risks.

“We need to think more broadly to solve the problem we face,” Culp said. “We’re not going to address the declining [water supply] without thinking about the significant investments that need to be made in tribal lands.”

Tribes entering the negotiations want the federal government and the states to give serious consideration to their visions for managing a shrinking river they have relied on for time immemorial.

“[Drought] is opening the eyes of people whose thoughts have been very restrictive of tribal water and haven’t wanted tribes at the table,” Cloud said. “This is an opportunity for us to be part of the solution.”