Late last year, when two months of scorching heatwaves and a drought pushed China’s electricity grid to the brink and caused severe power shortages in multiple provinces, it decided to turn back to coal.

Despite ongoing efforts to shift away from the dirty fuel and optimise its energy mix, the sudden plunge in hydroelectricity, China’s second biggest source of power, meant that something had to be done to add supporting capacity and prevent the nation from slipping into an energy crisis. When the Yangtze River, China’s longest waterway, dried up in parts because of extreme heat, the water supply for tens of thousands of people was affected, and factories in some provinces were forced to close to preserve electricity supplies.

Now, a new report from a Hong Kong-based think tank is saying that such dilemmas will likely confront all of Asia in the near future. Ten mighty rivers that flow through 16 Asian countries – known as the Hindu Kush Himalayan rivers – and that power coal and hydroelectricity generation are already impacted by climate change. The report warns that using coal to fuel development will further impact river flows, and wants China and India, both the region’s heavyweights, to take aggressive action to rein in emissions.

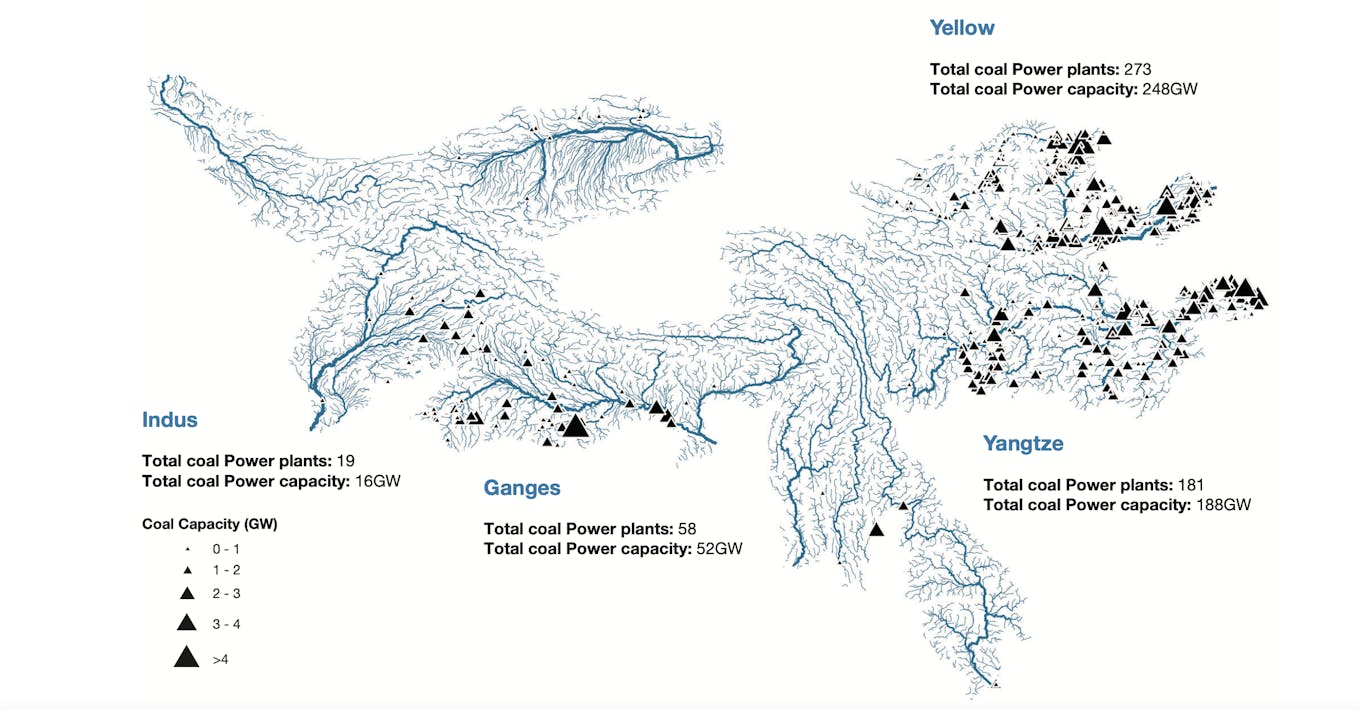

China “clearly has a role to play”, said the report published by non-profit China Water Risk. It currently has the largest coal-fired power fleet across the 10 river basins, accounting for 85 per cent in terms of the number of coal plants and total capacity across its mother rivers – the Yangtze and Yellow River – and the Tarim, which runs across the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Around 45 per cent of China’s power generation is both water-reliant and located in highly water-stressed regions.

“While coal may be the cornerstone of Asia’s energy policy for now, its expansion and ‘business-as-usual’ could raise water risks that could make its rivers run dry,” warned the think tank.

Coal-fired power generation requires water for cooling and driving steam turbines. With river basins facing varying degrees of water stress, coal fleets could be stranded earlier than expected.

Livelihoods at stake

Other than the Yangtze, the Yellow River and the Tarim, the report states that river flows of the Ganges, Indus, Irrawaddy and Mekong have all been affected by accelerating glacier and snow melt, as well as changing rainfall or monsoon patterns.

China and India “have the most power at risk” and “the most to lose if these rivers run dry”, said the report. China’s national energy dependence on the Hindu Kash Himalayan rivers is at 1,404 gigawatts (GW), the highest among the 16 countries that the rivers run through, with much of the installed capacity clustered in the Yellow River and Yangtze. Out of the 10 rivers, only the Amu Darya, a major river in Central Asia and Afghanistan, does not flow through China, and the other nine rivers support 44 per cent of China’s population and 30 per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP).

The Yellow River Basin coal fleet face the largest water stress exposure with 174 GW of its capacity installed in ‘high’ to ‘extremely high’ water stress areas. Image: China Water Risk

The Yangtze, also the world’s busiest inner waterway in terms of cargo flow, has the largest share of installed capacity at 373 GW, accounting for 27 per cent of China’s total power capacity. It carries a significant share of hydropower with just under two-thirds of China’s hydropower capacity. The Yangtze Economic Belt generates about half of the country’s GDP and is home to many free trade zones.

It is why China can make a significant difference for water security if it paves the way in setting the right energy policies, said the report.

‘Choose the right type of power’

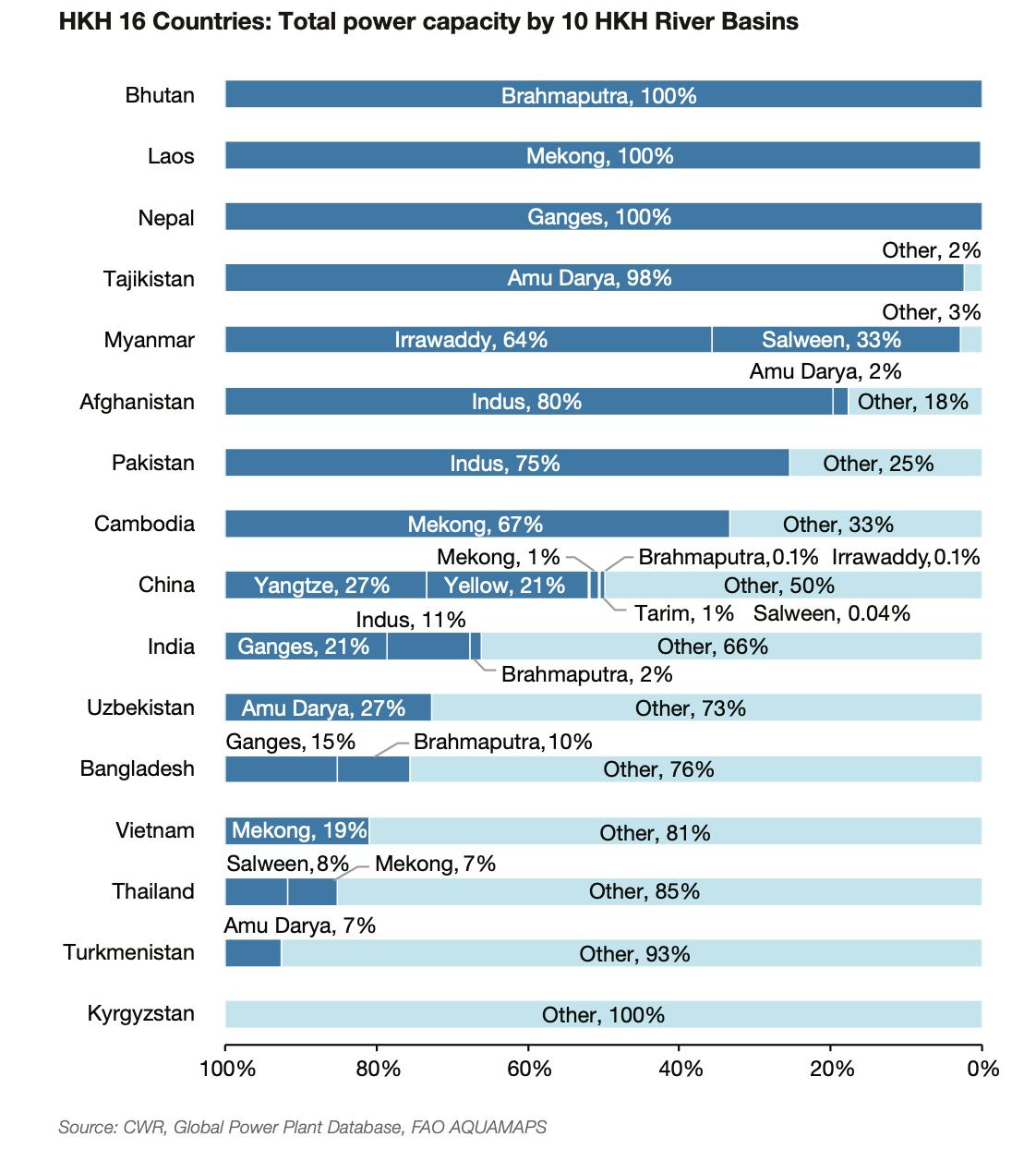

China, however, is not the most vulnerable nation, as its energy security is not tied to a single river, unlike some of the other Asian countries, said the report.

For example, Laos is 100 per cent reliant on the Mekong River, with its entire coal fleet in the Mekong river basin. Similarly, Nepal is 100 per cent reliant on the Ganges.

This graph shows the power reliance of 16 Asian countries on the 10 Hindu Kush Himalayan rivers. Bhutan, Laos and Nepal are the most vulnerable, as their energy security is tied to the fate of a single river. Source: China Water Risk

A key recommendation by the think tank in the report is for Asia to accelerate its deployment of renewables, including wind and solar, which it says will help alleviate pressures on scarce water resources as well as deliver a reduction in carbon emissions.

It also suggests that the use of less water-intensive plant cooling technologies, when deployed together with a renewable expansion, can reduce the water intensity of Chinese power generation by as much as 42 per cent.

The report notes that eight of the 10 Hindu Kush Himalayan rivers are transboundary, and decisions made by one country will affect others. It urged Asian countries to cooperate not only on water sharing, but on energy policies and economic planning, as a “wrong power mix” will take its toll on water resources.

BLOG

The Thirsty Dragon: Across Asia, China Has ‘Most to Lose’ If Rivers Run Dry

June 4th, 2023

June 4th, 2023

Via EcoBusiness, a look at how – across Asia – China has the ‘most to lose’ if mother rivers run dry and don’t recover from climate change:

This entry was posted on

Sunday, June 4th, 2023 at

9:46 pm and is filed under

China, Mekong River, Yangtze River, Yellow River. You can follow any responses to this entry through the

RSS 2.0 feed.

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

© 2025 Water Politics LLC . 'Water Politics', 'Water. Politics. Life', and 'Defining the Geopolitics of a Thirsty World' are service marks of Water Politics LLC.