BLOG

September 6th, 2020

Via The Diplomat, a sobering report on the Mekong River:

The miracle of the Mekong, where the pulsating force of the monsoon-driven river every year pushes its tributary to back up and reverse its flow into the great Tonle Sap lake in Cambodia, has again been disrupted and obstructed by dams, drought, and climate change.

“This is a terrible disaster for the whole Mekong region,” Thai academic Chainarong Setthachua declared. He told The Diplomat, “If we lose the Tonle Sap we lose the heart of the biggest inland fisheries in the world.”

The lake is a critical fishing ground for Cambodia, as well as supporting fish migrations along the entire Mekong. Back in 2014, Chheng Phen, the former director of Cambodia’s Inland Fisheries Research and Development Institute, told the New York Times, “If the Tonle Sap does not function,” he said, “then the whole fishery of the Mekong will collapse.” That is exactly what the Mekong region is facing today.

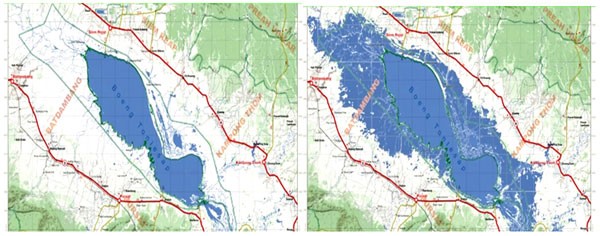

For the second year running, the wild pulsating waters of the Mekong have failed to work their traditional monsoon magic, which in normal times empowers the Tonle Sap lake to expand to five times its dry season size.

It is hard to exaggerate the extent of the unfolding disaster caused primarily by Chinese dams upstream, trapping both water and sediment that is vital to the healthy survival of the Mekong ecosystem.

The Tonle Sap crisis has also been greatly exacerbated by the two Lao dams – the Xayaburi dam and the Don Sahong launched in 2019 – that have blocked fish movement and sediment. Thailand and Malaysia are the developers and prime investors for those projects.

The Mekong-driven reverse flow had for centuries transformed the Tonle Sap lake, flooding what was once a sizable forest into part of the largest inland lake in Southeast Asia. In normal times the arrival of the rainy season flood and the reversal of the Tonle Sap tributary replenishes an amazing nursery of the fisheries by giving birth to the flooded forest of the lake.

But in 2020, like last year, too little water arrived and too late in the five-month rainy season from June to October. In 2019 the belated arrival of the flood pulse in mid-August led to the influx of shallow, warm, oxygen-starved waters and countless thousands of dead fish.

The same drought syndrome is happening again in 2020, with the damaged Mekong monsoon flow too weak push the Tonle Sap tributary back into the lake until mid-August (in a normal year it starts in June).

The Stimson Foundation’s Mekong specialist Brian Eyler recalled the wider impacts of last year’s disaster, now repeating itself: “The Tonle Sap’s 2.5 million fishermen took on higher levels of debt to cope with the extremely low fish catch. Now in 2020 it is maybe worse. These cycles of high debt and low fish catch can only be repeated so many times before the economy around the lake and likely the country itself begins to fall apart.”

Eyler, who is also the author of “The Last Days of the Mighty Mekong,” closely monitors China’s dams upstream. His research has now confirmed that “Chinese dams in July 2020 began to restrict an unprecedented amount of water while the countries downstream suffered drought in a repeat performance of last year.”

While the Chinese government and the Mekong River Commission (MRC) have claimed the primary causes of the drought are extra low rainfall and the El Nino effect, several studies have convincingly shown that these factors are far less important in causing the decimation of lower Mekong fisheries than the rapid expansion of hydropower.

A 2013 study from Aalto University in Finland conducted by Timo Rasanen demonstrated the impacts of upstream dams far outweighed climate change in its effects on the Tonle Sap lake.

Ian Cowx, director of Hull University’s International Fisheries Institute (HIFI) in the U.K., explained via email that the biggest long-term obstacle to the recovery of fisheries would not come from climate change and this drought, but rather from the dams upstream.

“All fish species are adapted to periods of droughts and floods,” he wrote. “The big issue here is the reduction in flows caused by Chinese dams, the Lower Sesan 2 dam [on a Mekong tributary in Cambodia], and the loss of the Hou Sahong channel because of Don Sahong dam.”

All these dams – not only the Chinese but also Thailand’s massive Xayaburi dam in Laos and the Malaysian-promoted Don Sahong dam – have changed the hydrology flow of the river and undermined the flood-pulse.

How Did the Mekong Come to This?

Many observers would expect it is the role of the Mekong River Commission — a consultative body of four lower Mekong countries — that should come to the rescue. After all, the MRC claims to protect the environment.

Yet scientists have issued numerous warnings about the rapid decline of Mekong to no avail. Even the MRC’s own research published in the 2018 Council Report warned that hydropower development would result in drastic fish losses through 2040, resulting in fish stocks declining dramatically. The total fishery biomass will be reduced by 35–40 percent by 2020, 40–80 percent by 2040, the MRC predicted.

But this alarming evidence of a massive fisheries decline and the imminent threat to the food security for 70 million people living in the Mekong basin did not lead to any declaration or guidance to member states on the need to put the brakes on hydropower.

In the words of Marc Goichot, a regional specialist in freshwater resources for WWF (World Wide Fund for Nature) based in Vietnam, “We predicted and witnessed the disaster in the making.”

“The problem is not one of technical and scientific understanding. It is one of governance. We need urgent action to improve the condition of the river,” he added.

But the response from MRC secretariat’s chief executive officer Dr. An Pich Hatda to the worst-ever crisis of the Tonle sap was a predictable call to all six Mekong countries “for more data and information sharing on their dam and water infrastructure operations in transparent and speedy manner.”

Goichot analyzed the lack of action in his interview with The Diplomat: “[I]nstead of focusing on how to save the river, the MRC focuses on activities such as collecting more data, monitoring and forecasting floods, droughts, and consultations,” he said. “The MRC could have prevented the crisis, but it failed in translating this (monitoring and science) into policies and an action plan to prevent it.”

The constant refrain of the MRC secretariat in answer to all criticism is to note that the group has no regulatory powers and only serves to facilitate dialogue between the four member states (Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam).

The MRC secretariat explained that in dam consultations “we seek measures to avoid, minimize and mitigate the potential transboundary adverse impacts of any proposed projects on the Mekong river.” This even as scientific evidence shows that large dams have inflicted unacceptable losses to the world’s inland fisheries, biodiversity, and food security. A range of Mekong experts have dismissed fish ladders, sediment and flushing schemes as lacking any scientific basis or track record of success on a tropical river.

Many Mekong NGOs consider that MRC-led stakeholder consultation process ignore the elephant in the room: The question of whether dams should be built at all. Should there be any more dams when hydropower has already left such a gigantically destructive footprint on the river? But the MRC secretariat guidelines try to block this question from being raised inside consultation forums. The implicit MRC bias toward accepting these dam projects has led to International Rivers and other environmental NGOs boycotting these stakeholder forums.

“We do not expect MRC to go beyond its mandate,” Goichot explained, “but good governance demands alerting MRC member states to the gravity and urgency of the crisis, and guidance on how to act on the dramatic decline in fisheries and sediment; and the sinking delta.”

Is the Mekong Doomed?

University of South Florida Professor Mauricio Arias, a leading hydrologist and participant in an International Symposium on Flood-pulse Ecosystems held in 2017 concluded that dams built upstream along the Mekong River, as well as the effects of climate change, have irreversibly harmed the ecosystem.

“We’re going from a wild Mekong to a closed river system that’s boring and dead,” Arias said. He pointed to the cautionary tale of the similarly heavily dammed Colorado River in the United States.

It seems that the MRC and some regional governments do not mind that the Mekong is heading toward a similarly tragic fate.

Senglong Youk, the local fisheries NGO leader, is deeply worried about the Mekong’s future. “It’s very hard to dream for the recovery of the fisheries in the Great Lake. Some people are illegally clearing flooded forest. Other people consider using it as [the] site of a giant soccer field.”

One narrative is clearly all about gloom and doom, which prompts Mekong lovers to feel despair as we all bid a fond farewell to a free-flowing and mighty Mekong.

However, an alternative scenario also beckons with a number of big “ifs” attached. If economic sense prevails, and all parties settle for solar and wind power as the best energy pathway, and if future Mekong dams in Laos are suspended as obsolete, then a recovery plan becomes a real possibility.

Construction of the Luang Prabang, Pak Beng, and other dams in the Lao pipeline are now largely dependent on whether Thailand signs an agreement to buy the electricity. Thailand built and funded the Xayaburi dam in Laos and agreed to import 95 percent of its electricity. If Bangkok does not buy, the Luang Prabang dam almost certainly will not go ahead. This gives Bangkok’s policymakers a pivotal role in deciding the fate of the Mekong.

Thailand has one of the highest energy surpluses in the region, bringing in 40 percent more electricity than actual consumption. Independent analysts claim the figure is around 60 percent.

Whatever happens, the prospect of Tonle Sap’s fisheries recovering their average of 300,000 tons a year is hard to imagine. Goichot of the WWF commented, “At this stage, repairing the damage already done to the Mekong will be long and costly; but there is no other way forward.”

Goichot advocates for the WWF-launched Emergency Recovery Plan for the world’s freshwater biodiversity. “This WWF plan applies to the entire planet, but it is even more urgent in the Mekong than in most other places in the world.”

Meanwhile, some 2.5 million people like Senglong Youk are in dire need of for funds to save their Great Lake. The effort should attract interest from many U.N. agencies that have a stake in the preservation of the Tonle Sap.

Could the MRC help? I asked the Tonle Sap-based leader. Senglong Youk replied with his “message to the MRC”: “you can help first by stop building hydropower dams.”

This is a popular cry among the suffering communities of the river, but a viewpoint that has been censored inside the MRC consultative stakeholder forums on dams.

U.S.-based Vietnamese author and ecologist Dr. Ngo The Vinh pointed out the crucial role the lake has played in Cambodian history. “The Mekong River and Tonle Sap Lake are the birthplace of the ancient as well as modern Khmer civilization. Regrettably, the survival of the Tonle Sap Lake itself is in doubt,” he said.

How will Cambodia’ s Ankorian ancestors judge todays rulers, who have weakened Tonle Sap by damming the Lower Sesan 2, a vital tributary of the Mekong? What would they think about a Mekong River Commission that contents itself with data and monitoring rather than taking action?

Such is the importance of the Great Lake that it has been dubbed as the “beating heart of Cambodia.” But the hydro-hungry leaders of MRC member states do not seem to care or be aware of the Tonle Sap’s critical state.

Will the Cambodian government, the MRC, and donor countries come up with an intensive care and rescue plan to save this wonder of the world and keep the Mekong’s heart beating? If they fail to deliver on their duty of stewardship and protection of this Cambodian treasure, this is indeed the last farewell to the mighty Mekong.