BLOG

August 11th, 2016

Via The Economist, a look at China’s Three Gorges dam:

OUTSIDE China, the monster Three Gorges dam across the Yangzi river is one of the most reviled engineering projects ever built. It is blamed for fouling the environment and causing great suffering among the 1.2m people who were relocated to make way for its reservoir. Inside China, officials insist that the dam is an “unsung hero” (in the recent words of the Yangzi’s chief of flood control). But controversy over the project occasionally flares. Amid the country’s worst flooding in years, it is doing so again.

The Communist Party took enormous pride in the completion of the Three Gorges dam a decade ago; officials said it would play a vital role in taming a river which, when it flooded, often claimed hundreds or thousands of lives. Recently, however, censors have permitted a few ripples of complaint to disturb the glassy surface of state-run media. Online critics have asked whether the dam has failed to protect cities from flooding or whether it has caused earthquakes—and have not had their posts deleted. Granting permission to complain may seem surprising. But officials have reason to feel confident. The much-denounced dam seems to be passing its first big test as a flood barrier.

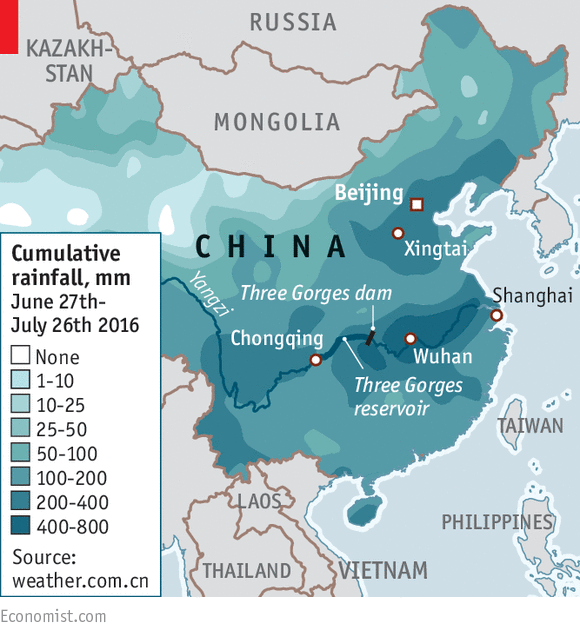

This season has been one of the wettest in China’s recent history, with 150 towns and cities suffering record amounts of rain. The Yangzi basin has been particularly hard hit. In the week to July 6th Wuhan, a giant city downstream from the dam, received 560mm (22 inches) of rain, its biggest ever downpour (residents are pictured on a temporary bridge).

China’s most recent experience of weather like this was in 1998, which was also the last time El Niño, a shift in the weather patterns of the western Pacific, had a big impact on the world’s weather. That summer the Yangzi burst its banks, causing more than 1,300 deaths. So far this year fewer than 200 people have died in the river’s basin.

One big difference is that in 1998 the Three Gorges dam was still under construction (it went into full operation in 2012). By July 24th it had held back about 7.5 billion cubic metres (260 billion cubic feet) of potential floodwater, which would have compounded disasters caused by torrential rain in the middle and lower reaches: some of the heaviest rains have occurred downstream from the dam. It is too soon to declare victory over the floods. The rainy season is only halfway through and more downpours are expected in August. But so far, as a method of flood control, the dam has done more or less what it was supposed to.

That doesn’t necessarily justify the project. One of the most important criticisms of it, by the late Huang Wanli, a hydrologist at Tsinghua University in Beijing, is that so much silt will eventually build up behind the dam that it will have to be taken down, leaving the Yangzi basin worse off than if the barrier had never been built. The region in which the dam stands is also one of the world’s most seismically active. Geologists worry that the weight of water in the sinuous reservoir, 600km (370 miles) from end to end, and the rise and fall of it, is causing more frequent tremors along the fault lines. Even small earthquakes can cause perilous landslides.

Considered purely as a means of flood control, the dam is a mixed blessing. The silt-free water that gushes through it fails to replenish embankments downstream, thus weakening them as flood barriers (several have collapsed this year). Below the dam, the water now runs faster; it has scraped away and lowered the Yangzi’s bed by as much as 11 metres, according to Fan Xiao, an independent researcher who has written several reports for Probe International, a Canadian NGO. As a result, nearby wetlands drain into the river, damaging their ability to act as sponges during a flood.

In 2000 another academic at Tsinghua, Zhang Guangduo (who had done the environmental feasibility studies for the dam), told the man in charge of building the barrier that “perhaps you know that the flood-control capacity of the Three Gorges Project is smaller than declared by us,” according to leaked documents. Peter Bosshard of International Rivers, an environmental NGO, asks whether it was wise to spend so many billions on one project, rather than strengthen flood-protection measures all along the Yangzi.

That point has been borne out by the many failures of local flood-control measures that have also occurred this year. In July parts of Wuhan’s metro system filled with water. This seems to be the result of bad management or corruption. According to People’s Daily, a party newspaper, only 4 billion yuan ($600m) of the 13 billion yuan allocated to improving drainage in the metro was actually spent. Local media say that one of the people responsible for drainage projects in the city is under arrest for taking huge bribes.

Such problems have been exacerbated by urban expansion. Wuhan used to have more than 100 lakes, but it has lost two-thirds of them to construction sites since 1949. The city’s wetlands have been gobbled up, too. Those that remain are too small to store flood waters. It is a relief that far fewer people have died in floods along the Yangzi this year compared with 1998. But it is no indication of the basin’s broader environmental health.

The Three Gorges dam has a historical parallel. In 1928 a tropical hurricane caused Lake Okeechobee, in central Florida, to flood, drowning 2,500 people in the southern half of the state. Determined that such a thing would never happen again, America’s Army Corps of Engineers over the next few decades drained much of the Everglades, which then covered much of the southern part of the state. No human disaster has recurred but the Everglades is a shadow of its former self and conservationists are battling to save it from destruction. The Yangzi is in danger not only from floods but from its flood controls.