What’s new??Cameroon’s Far North, the country’s poorest region, is experiencing recurrent inter-communal frictions over water reserves. As national and local authorities try to contain fighting between Choa Arab herders and Musgum fisherfolk, other ethnic groups are at risk of being drawn into a conflict that has displaced tens of thousands.

Why did it happen??The Far North is grappling with militant raids, as well as deep grievances triggered by poor governance and increasing food scarcity. Erratic rainfall due to climate change has intensified competition between ethnic groups over water and land.

Why does it matter??Cameroon can ill afford a new cycle of inter-communal violence in the remote but densely populated Far North, which lies in the Sahel belt. Its forces are overstretched fighting insurgents elsewhere in the country.

What should be done??To help resolve tensions before they escalate, authorities should increase the number of early warning committees in the Far North and strengthen preparedness for climate shocks. They should make water and land management more inclusive and ensure that the region’s people have access to better justice services.

BLOG

April 27th, 2024

Via Crisis Group, a report on water conflict in Cameroon:

I.Overview

The spectre of deadly fighting between Choa Arab and Musgum groups hangs over Cameroon’s Far North, due in part to competition over water and land. A dispute over the Logone River waters sparked a round of conflict in 2021, reviving years of bitter political rivalry in a region battered by the Islamist insurgency Boko Haram, drought and flooding. The government has tried to prevent the Choa Arab-Musgum tensions from spilling over, but with only partial success. Between 2021 and 2023, a dozen other clashes linked to resources temporarily displaced some 15,000 people of other ethnicities in the area. As the war with jihadists and the fighting in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions are taxing government forces, Yaoundé would likely struggle to contain a new wave of violence. With donor support, it should strengthen early warning mechanisms for conflict and rainfall, as well as reform water and land governance to improve public access and ensure fairer dispute resolution. It should also incorporate climate security measures in its reconstruction program for the Far North.

The Choa Arab-Musgum conflict is rooted in longstanding grievances. Many Musgum are fishers and farmers who often dig basins on the floodplains of the Logone River to retain fish and water, which they use to irrigate their fields; meanwhile, many Choa Arabs are cattle owners. Cows sometimes get trapped in the marshy canals, suffering injury or death. Both groups fear their livelihoods are under threat: the Musgum want to keep digging basins while the Choa Arabs want the practice stopped. This disagreement has escalated into a broader ethnic feud. Musgum and other sedentary groups complain that administrators favour Choa Arabs in disputes about water, land and chieftaincies. At the same time, changing rainfall patterns are harming land across the Far North, with recurring droughts and floods diminishing soil fertility. As a result, farmers are harvesting fewer crops and communities are struggling to find enough potable water. Many residents are wary of existing judicial and governance systems, sometimes leading them to try resolving resource disputes through violence.

The Cameroonian government has striven to contain the Choa Arab-Musgum conflict.The Cameroonian government has striven to contain the Choa Arab-Musgum conflict, deploying security forces to prevent other communities – Kotoko, Massa, Fulani, Kanuri and Sara – from getting drawn into the clashes. Cameroon has also worked with Chad to monitor developments along the Logone River, whose waters the two countries share. Yaoundé has allowed humanitarian organisations to set up camps for displaced people in Maroua and Bogo in the Logone-et-Chari division. The government has also discouraged further violence by arresting troublemakers, imposing curfews and convening political, religious and traditional elites for talks.

Despite these efforts, the risk of inter-communal violence in the region remains high. Clashes between Choa Arabs and Musgum resumed in November 2023, while tensions are rising among other groups in the Mayo-Sava, Mayo-Tsanaga, Mayo-Danay and Diamare divisions of the Far North. The Boko Haram and Islamic State in West Africa Province jihadist insurgencies could also inflame tensions. Officials are concerned that local people could use the jihadists’ trafficking networks to buy small arms, driving further violence. These insurgencies also continue to encroach upon lands used for farming, fishing and herding, rendering many areas unsafe. Thousands of displaced people are now forced to compete over the same water and pasture in northern Cameroon and Nigeria’s Borno state.

To find solutions, the authorities need to address the conflict’s roots, improving access to water and land. While ethnic tensions have long plagued the region, the poor management of water and land exacerbated by climate stresses has made matters worse. The immediate priority for Cameroon should be to bolster its existing early warning mechanisms, such as local crisis committees created after the 2021 clashes and weather forecasts prepared by the National Climate Change Observatory. In the medium term, local and national authorities should ensure that their ambitious development plans for the region are environment-, climate- and conflict-sensitive. In particular, they should establish a system for managing water points that includes representatives of all ethnic groups, as well as women and young people. They should also seek to boost citizens’ trust in the justice system and create a fund to provide individual or community-based compensation for victims of clashes.

II.The Choa Arabs and Musgum: The Casus Belli

The Far North is one of Cameroon’s most populous and least developed regions, with more than three million inhabitants and a poverty rate exceeding 74 per cent.1 Despite the hardships its citizens face, the region is politically important to President Paul Biya because of its large voting-age population and its unwavering support for the ruling Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement.2

Sedentary, nomadic and semi-nomadic groups have lived side by side in the Far North for centuries, but not without friction. Inter-communal relations are often strained, with some disputes dating back decades.3 Ties to kin in neighbouring Nigeria and Chad tend to foster a strong sense of ethnic loyalty straddling national borders, frequently raising the stakes of local flare-ups when they erupt.4 Conflict broke out between the Choa Arabs and the Kotoko (often supported by the Musgum) in the 1970s and 1980s, while in the early 1990s they fought for political dominance during Cameroon’s transition to competitive electoral democracy.5

The Far North is situated in the Sahel, where temperatures are rising one and a half times faster than the global average, according to the UN.6 Experts say the Far North, like the rest of the Sahel, is highly vulnerable to weather shocks.7 The climate in the Logone-et-Chari division at the region’s northernmost tip is particularly harsh. The division’s capital, Kousseri, is on average the hottest city in Cameroon.8 During the dry season, which typically runs from October through June, temperatures peak at around 40°C and evapotranspiration – the loss of water from both the soil surface and plants, a process that hurts agricultural productivity – increases.9 High temperatures along with erratic rains shrink water available for fishing communities and pasture for herders.10 In 2021, a severe drought made conditions even more difficult than usual.11 The rainy season typically lasts three to five months, bringing precipitation that replenishes the soil but also an increasing number of downpours that cause devastating floods.

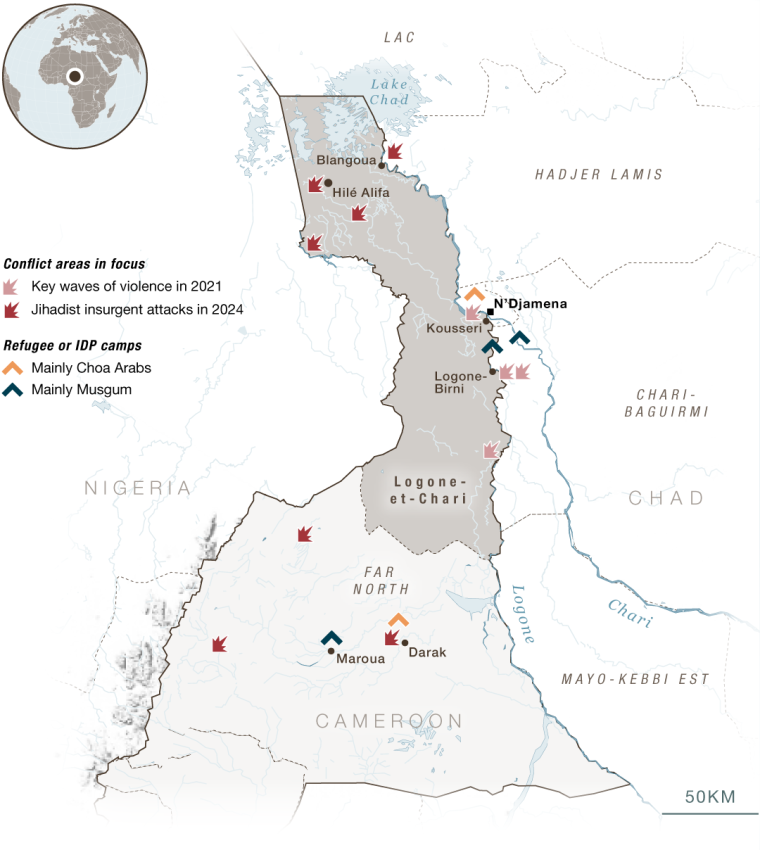

Dozens were killed and 100,000 displaced over 2021-2022 in conflict between Choa Arab and Musgum groups in a region also suffering jihadist attacks. Crisis Group research, OSM, Copernicus. CRISIS GROUPA.Drowned Cattle and the 2021 Clashes

The Choa Arab-Musgum conflict illustrates how climate stress can heighten inter-communal tensions. During the dry season, Musgum fisherfolk in the Logone-et-Chari division often dig large basins on the floodplains of the Logone River, a low-cost albeit labour-intensive way to retain water and fish.12 As the dry seasons get hotter and drier, they are digging more of these basins, which can be hazardous to cows. In August 2021, a Choa Arab herder’s cow drowned after getting stuck in one such basin dug by a Musgum.13 Incensed Choa Arabs in the town of Logone-Birni gave the local Musgum an ultimatum to fill the basins with soil to prevent other cattle from stumbling into them. When the Musgum refused, the Choa Arabs attacked.

The skirmish rapidly degenerated into a series of retaliatory assaults. The violence spread throughout the Logone-et-Chari division, including Kousseri, where the Logone River cuts a natural border with the Chadian capital, N’Djamena. The nearby Mayo-Danay division also saw fighting between Choa Arabs and Musgum.14 The two sides attacked each other’s villages, using knives, bows and locally manufactured guns.15 In some instances, they also sexually assaulted or killed women as a form of collective punishment before setting houses ablaze.16

Although men perpetrated the violence, women played a role in the conflict at times. Locals told Crisis Group that a small number of Musgum women gathered intelligence during the clashes.17 Some women told Crisis Group that they tried to dissuade men from fighting.18 Several women moved entire families in canoes across the Logone River to safety in Chad, helping to evacuate an estimated 11,000 people, mostly women and children.19

As August’s violence subsided, local authorities imposed a general curfew and banned gatherings of more than ten people. But the two communities were already planning their next moves, while taking steps to protect the most vulnerable from future attack.20 For example, Musgum evacuated additional groups of women and children across the Logone River to stay with kin in Chad.21 Both ethnic groups also used the river to smuggle weapons and ammunition from Chad as men from elsewhere in the region travelled to Logone-et-Chari division to swell the fighters’ ranks.22 The two sides came to blows again in September and December.

Local authorities took several measures to curb the violence. In December, administrators banned boat traffic on the river. In Kousseri, officials set up a twenty-member crisis committee comprising Choa Arab and Musgum representatives – ten members of each group – to organise an open dialogue. The committee struggled to make progress, however, as fresh fighting broke out in town just days after an early December reconciliation meeting.23

According to the authorities, around 100 people died in the inter-communal clashes between August and December 2021. But residents told Crisis Group that this figure is probably an undercount, given how much destruction occurred and how long it took for security forces to arrive to calm tempers. In addition, eyewitnesses say scores of men, women and children drowned trying to swim across the Logone River. These deaths are likely not included in the official toll.

About 100,000 people, mainly women and children, fled the violence [in the Logone-et-Chari division], creating humanitarian emergencies in Cameroon and Chad.In total, about 100,000 people, mainly women and children, fled the violence, creating humanitarian emergencies in Cameroon and Chad. The authorities in N’Djamena were first to raise the alarm. In December 2021, President Mahamat Déby Itno said Chad had taken in nearly 30,000 Cameroonians.24 The refugee influx prompted Déby to post guards along the Logone River and to block local Choa Arabs and Musgum from sending weapons to Cameroon.25

Yaoundé had kept silent until then, likely because acknowledging the violence might have undermined the government’s preferred narrative of peace and stability in the Far North.26 Regional officials toured the Logone-Birni area a few days after the clashes subsided, while security forces deployed in more than a hundred villages in the area. Despite their small numbers and the flooded terrain, troops managed to disperse most fighters and arrest hundreds, mostly men.27 The troops held the detainees in Kousseri, sending around 100 of them to the regional capital Maroua toward the end of the year in a bid to prevent jailbreaks and marches outside the prison as both Choa Arabs and Musgum took to the streets. New violent protests erupted in Kousseri in December 2021, with Musgum demonstrators demanding the detainees’ release, arguing that members of their ethnic group had been the main targets of the roundups.28 In January 2022, troops quashed similar angry protests in Kousseri by Choa Arabs in support of a former mayor in the region, Acheick Aboukresse, who had been arrested.29

The authorities allowed humanitarian agencies to establish camps for some 15,000 displaced people in Maroua and Bogo in the Diamare division, away from the main conflict zone and guarded by unarmed vigilantes.30 (The camps are still in place today.) The UN refugee agency and foreign non-governmental organisations obtained emergency funding to distribute food aid and other items, such as hygiene and sanitation kits, in displacement camps in Cameroon and Chad. But most needs have remained unmet.31 There are reports of young Choa Arab girls fending for themselves on the streets of Maroua, where they are vulnerable to sexual violence and trafficking.32 Both communities harbour suspicions that culprits in violence on the other side have benefitted from impunity.33

Aid agencies have also been slow to account for the Choa Arab-Musgum conflict in their regional programming.34 Only in 2023 did the UN Peacebuilding Fund help Cameroon’s justice ministry and local authorities form early warning committees (comités villagéoises d’alerte et concertation, in French) out of revived traditional courts. The purpose of these committees is to monitor tensions within communities, resolve disputes and report threats of violence to administrative and security officials. In November 2023, these committees helped avert a new cycle of violence by tipping off the army that it should dispatch patrols to areas where tensions were brewing.35 But there are too few of them. Thus far, committees have been set up in just ten of the approximately one hundred villages where the 2021 fighting took place, mainly in the Logone-Birni sub-division.36 UN officials pressed local administrators to include women in these committees, but of 167 members in the ten villages, only 23 are women.37

B.Sporadic Clashes and Continuing Tensions

Since 2022, an uneasy calm punctuated by outbursts of violence has settled in the Logone-et-Chari division. The Choa Arab and Musgum communities are increasingly segregated from one another, and when tensions arise over access to resources, they escalate quickly.

Data show that twelve of eighteen communal conflicts in the Far North between January 2022 and November 2023 were directly related to water, land or both.38 For example, on 16 September 2022, Kirdi farmers clashed with Fulani herders in Adakele, Mora town (Mayo-Sava division) after weeks of disputes over grazing and agricultural land, with the two sides destroying each other’s property. On 22 July 2023, Christian and Muslim groups fought over land in Warba village, Tokombere town, Mayo-Sava, leaving four men dead and displacing about 4,500 people.39 On 11 August 2023, residents of Doukouroye and Silla in Kai Kai, a commune in Mayo-Danay division, came to blows over ownership of a rice farm, resulting in four deaths.40On 19 September 2023, Choa Arabs from Malia and Kanuri from Ndiguina also battled over farmland in Waza.41

Many residents worry that a fresh cycle of violence might draw in ethnic groups that have remained on the sidelines of the Choa Arab-Musgum conflict.Many residents worry that a fresh cycle of violence might draw in ethnic groups that have remained on the sidelines of the Choa Arab-Musgum conflict. 42 Some communities lean toward the Musgum and others toward the Choa Arabs. The Kotoko, for example, are mostly sedentary, like the Musgum, with whom they have social and cultural ties; the Fulani, who are typically herders, feel closer to the Choa Arabs. Some semi-nomadic Fulani considered backing the Choa Arabs in the 2021 conflict but decided against joining them because the villages where fighting took place were difficult to get to.43 On 6 October 2023, Kotoko and Choa Arabs clashed in Makary, Logone-et-Chari. After the incident, Choa Arab leaders reportedly met in the nearby town of Goulfey to organise reprisals against the Musgum and Kotoko.44 The government managed to ward off a confrontation by sending soldiers to five towns where inter-communal tensions were high.45

Authorities are dutifully monitoring the situation, but so far, they have done little to address the underlying problems, and people are still living in fear. The government has encouraged peacebuilding through talks among traditional and religious leaders. The dialogues usually exclude women and youth leaders, whether or not they or their families have been victims in the clashes, as well as the perpetrators of violence. These initiatives have generally fizzled out. After a peace tour by members of the region’s elite in August 2021, violence kicked off again the following month.46 In another instance, local administrators cancelled a May 2023 peace meeting called by the speaker of the National Assembly, who is from the Far North, fearing it would rile the population.47 In June 2023, several young Musgum left a work site in the village of Arkis, near Kousseri, where a project led by the French development agency employed 150 young people, over concerns for their safety in this predominantly Choa Arab locality.48

Efforts by traditional and religious leaders encouraging the displaced to return have likewise gone largely unheeded.49 The number of displaced people fluctuates as tensions ebb and flow, while reliable figures are hard to come by, given that aid agencies lack the capacity to keep track of inter-communal conflict. Still, many displaced in towns like Maroua and Kousseri told Crisis Group that they have little to go back to. Several Choa Arabs said they are still recovering from the trauma of losing family members, land and livestock. Other displaced people said they worry about fresh violence in their hometowns. Yet others are seeking clarity about land ownership before considering returning.50 Those who have returned now stay primarily among their own kin, whereas before the clashes there was more interaction between the two communities.51 Genuine civic life has crumbled in the hardest-hit towns.

III.The Far North’s Vulnerabilities

More people in the Far North depend on farming, fishing or herding for their livelihoods than in any other part of Cameroon, making the region particularly vulnerable to fighting that pushes people away from fields, streams and pastures. In the past decade, food insecurity has climbed significantly due to attacks by Boko Haram and then splinter groups. More than 80 per cent of the 700,000 people in the Far North who were displaced as of February 2023 fled due to jihadist violence.52 The insurgency thus worsened the region’s already vast economic problems.53 At the same time, the Far North suffers more droughts and deadly floods than anywhere else in the country. A mix of these and other climate concerns – unpredictable rainfall and uncertainty about the planting season – has reduced access to potable water and diminished food reserves.54 Of the 3.5 million people facing acute food insecurity in Cameroon in 2023, nearly 1.6 million resided in the Far North, a 33 per cent increase from 2022.55 All these factors contribute to fears that renewed inter-communal clashes could aggravate the humanitarian crisis.

A.The Boko Haram Threat

Boko Haram first attacked Cameroon in March 2014, but the group had sent members into the Far North at least three years earlier.56 Historical neglect by the state and cultural similarities with north-eastern Nigeria, where the insurgency first emerged, made the Far North vulnerable to jihadist infiltration, as did the region’s smuggling networks, highway banditry and crime of all kinds, particularly in border zones. Militants also used toeholds in Chad and Niger to recruit in those countries, appealing to ethnic, commercial and religious ties, while exploiting inter-communal tensions along the frontiers where they operated.

Boko Haram’s first attacks in Cameroon were mostly small-scale, if often deadly, targeting army checkpoints and patrols, as well as public roads, schools and markets. At times, the group deployed young girls it had abducted as suicide bombers. Starting in 2014, the four Lake Chad countries – Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria – all sent troops to the affected areas under the banner of the Multinational Joint Task Force.57 Yaoundé also sent extra soldiers to the Far North, while local authorities imposed curfews and mounted sting operations to find suspected militants. Although the epicentre of Boko Haram violence remained in Nigeria, the number of raids in the Far North rose steeply between 2015 and 2017 before tapering off due to these security measures and the group’s changing tactics. Overall, attacks by Boko Haram and, later, its breakaway faction Islamic State West Africa Province have caused thousands to flee their homes in the Far North, with deleterious effects on education and health care in the region.58

Today, militants raid the Far North primarily to steal food, supplies and other necessities. Particularly around Lake Chad, jihadist incursions have made many farmlands, fishing areas and pastures dangerous for locals, with combatants carrying out hit-and-run attacks in the Mayo-Tsanaga, Logone-et-Chari and Mayo-Sava divisions.59 The deadliest incident to date occurred in June 2019, when militants killed twenty soldiers and sixteen civilians, mostly fisherfolk, on Darak island in Logone-et-Chari.60 In 2023, fighters used a range of strategies to get food, money or water, for example by extorting “taxes” from fishing communities, stealing cattle and grain, or forcing residents to abandon water points.61 Many people have moved farther south in the division, aggravating stresses on the residents by increasing competition over land and worsening food insecurity.62

Observers worry that the jihadist threat in combination with simmering inter-communal tensions could make conflicts deadlier.Observers worry that the jihadist threat in combination with simmering inter-communal tensions could make conflicts deadlier. In the past, Boko Haram exploited social and economic hardship to recruit and acquire local logistical help.63 As frictions between Choa Arabs and Musgum increase in the face of resource scarcity, young men in particular could become more vulnerable to recruitment into, or collaboration with, jihadist groups, which often use the proceeds of local extortion rackets to provide for their recruits.64 In addition, weapons are easily available in the region. One official expressed concern that disgruntled groups could tap into arms smuggling networks already used by militant groups if tensions boil over again.65 Others worry that communities might resort to creating larger self-defence militias involving other affiliated ethnic groups living in Cameroon, but also across the border in Chad and Nigeria.66

In response to Boko Haram’s attacks, President Biya announced a reconstruction program for the region in December 2019. The Programme Spécial de Reconstruction et de Développement de la Région de l’Extrême Nord was designed to build reservoirs, roads, schools and clinics. Acknowledging the region’s climate-related problems, as well as the militant threat, the program aims to counter both by developing livelihoods and strengthening the region’s resilience to extreme weather events.67 It was a commendable step, but nothing much happened over the next three years as the government selected the program’s administrators. In October 2023, Yaoundé appeared to move to the next stage, saying it planned to invest a whopping $3 billion in the region over five years.68

Many Cameroonians are sceptical as to whether the government will complete the program. When its coordinators toured the Far North in late 2023, bad roads, flooding and insecurity prevented the delegation from reaching the Logone-et-Chari division, the area most affected by resource-related conflict. Moreover, the ambitious budget may be a veiled attempt at securing votes ahead of the presidential election scheduled for 2025. Still, if carried out as planned, the program could help stabilise the region and bring much-needed relief to its residents.69

B.Water Scarcity and Floods

Getting water is an everyday struggle for people in the Far North. A staggering 44 per cent of boreholes and 61 per cent of wells in the country are situated in the Far North, illustrating the dearth of naturally accessible water sources despite the region’s proximity to Lake Chad.70 By contrast, residents of Cameroon’s southern regions get most of their water from catchments perennially filled by rivers and springs. Cameroon is marked as “water insecure” in a recent UN report, due to poor scores in health, sanitation, overall water availability and quality. This national ranking might be worse if the assessment metric considered the Far North alone.71

Lake Chad, which shares a long boundary with the Far North, has become less reliable as a water source. It is one of Africa’s largest freshwater lakes, fed by the Logone and Chari Rivers, but its surface area varies greatly by season – and from year to year. Recurrent droughts in the 1970s and 1980s dramatically reduced the lake’s volume. Although the volume rose substantially between 2018 and 2022 ? notwithstanding a 2021 drought ? water recovery is periodic, with variations in annual rainfall intensifying competition for water among the millions of people who live in the lake basin.72

Besides droughts, the Far North is increasingly suffering from floods. Data suggest that floods and heavy rainfall were responsible for uprooting nearly 20 per cent of the 700,000 displaced people registered in February 2023.73 In 2022, for example, floods in the Far North affected more than 258,000 people, in Logone-et-Chari, Mayo-Tsanaga and Mayo-Danay divisions.74

Countries have tried to ease the water-related stresses in the region. Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria established the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) in 1964, with the Central African Republic and Libya joining in 1996 and 2008, respectively. The commission’s role is to manage the lake and its associated waters, protect the area’s fragile ecosystems and promote development.75 One of its most important interventions was the development of an early warning system for flooding in the Logone basin, which covered Cameroon and Chad between 2016 and 2020.76 The commission set up twenty hydrometric and meteorological stations to bolster early flood detection, part of a project in which the World Bank funded a dyke 70km long on the Logone River and another 27km long on Maga Dam.77 These stations were mainly confined to areas where Cameroon’s state-owned company Semry was developing rice farms.78

But, even by the accounts of LCBC personnel, the environmental monitoring network around Lake Chad is under-funded and poorly run.79 The commission has completed several projects in Cameroon, including planting trees to improve land quality in the Far North, as well as building a handful of clinics and schools.80 Yet its role in the Far North’s water crisis has largely been limited to urging Cameroon and other member states to monitor the situation and adapt to climate variability.81

In addition, Cameroon established the National Climate Change Observatory in 2009 with the goal of assessing the socio-economic and environmental impact of climate change and proposing measures to mitigate risks. Its scientists regularly conduct fieldwork in the Far North and publish seasonal alerts on local water and temperature profiles, with three- and six-month forecasts.82 In theory, its work underpins environmental and resource planning in the region (as it does in the rest of the country). In practice, however, it lacks the clout to influence government policies, and economic planners and administrators rarely consult it.83 Furthermore, the observatory and government departments with portfolios directly related to water management ? such as fisheries and livestock, agriculture and rural development ? often fight over turf regarding the scope of their responsibilities.84 Despite the observatory’s important early warning work, there is little evidence that local administrators incorporate its findings in their policies.85

C.Opaque Land Management and Corruption

Poor land and water management coupled with pervasive corruption risk accelerating the impact of climate stresses in Cameroon’s Far North.86 Land management is often opaque. Local administrators and traditional rulers have authority to allocate land, but it is often unclear who has the final say in actual sales.87 As a result, a piece of land may be allocated or sold to two or more different people before the onerous process of issuing a title deed gets under way. Mistrust of land administrators is therefore widespread. In addition, experts told Crisis Group that laws and practices governing land tenure, water and livestock are outdated.88 For example, the 1998 Water Code makes no provision for regulating competing water usage, which leaves local authorities on shaky legal ground when they have to adjudicate disputes over water.89 Maps of grazing corridors are likewise in urgent need of updating to account for demographic change and loss of vegetation.90

Corruption at all levels of government compounds the problem, as do socio-economic divides.91 For example, Musgum farmers consider themselves to be rightful landowners, perceiving the majority Choa Arabs as newcomers with no legal claim to the area. Many think of the Choa Arabs as concerned only with making money.92 Such assumptions feed the widely held belief among Musgum that Choa Arabs bribe administrators to acquire land in Musgum territory and get their kin appointed as traditional rulers.93 For their part, Choa Arabs argue that the Musgum unfairly exclude them from the floodplains along the Logone River, which leaves them with no option but to use their demographic and financial sway to obtain land in the area or to convince officials to decide land disputes in their favour.94

Women from both communities face additional obstacles in obtaining and managing land and water as a result of patriarchal practices. Both Choa Arab and Musgum men take a dim view of women owning land and exclude women from debates on land and water management, the outcomes of which nevertheless have a direct impact on women’s activities.95 Men typically own farmland and water points, while women irrigate crops and look after water sources, such as canals. Women and children also fetch water for domestic use, as is customary throughout Cameroon. In some areas in the Far North, women and children walk 8km to the closest water point, often leaving home in the middle of the night in order to get back in time to prepare a meal.96 This division of labour likely contributes to the low literacy rate in the region, particularly when it comes to girls.97 Yet women are excluded from water management committees and rarely consulted when disputes arise.98

IV.Building a More Peaceful and Resource-secure Region

Cameroon’s response to inter-communal conflict in the Far North has thus far been mostly a band-aid.99 Security forces have helped prevent large-scale violence and capped tensions in the Far North. Authorities mobilised communal leaders to set up platforms for dialogue and allowed humanitarian organisations to give locals food and temporary housing. Worthy and at time effective as they have been, these steps have largely focused on preventing escalation in the Choa Arab-Musgum feud rather than addressing underlying climate shocks or simmering tensions among other ethnic groups in the Far North.100 Keeping a large number of soldiers in the region is not a long-term solution, given that the military is already stretched by its battles with insurgents elsewhere.101 The Far North remains sorely underdeveloped, while climate change threatens to make arable land, pasture and water even scarcer as time goes on. The Cameroonian authorities should develop policies that address drivers of inter-communal conflict. Helping prepare the region to withstand extreme weather events can help.

A.Averting Violence and Helping the Vulnerable

The Cameroonian authorities should build on existing conflict prevention measures to avert more inter-communal violence in the Far North. The anger generated by the 2021 conflict is still palpable in the Logone-et-Chari division, raising the prospect of renewed clashes between Choa Arabs and Musgum or among other ethnic groups. Local authorities should urgently roll out additional early warning committees in all the affected villages around Logone-Birni. These committees, which should include women and youth leaders, would ideally help manage ethnic tensions, mediate minor disputes and report major threats to local administrators, security forces and judicial authorities.102 To overcome the challenges faced by past peace efforts, authorities should ensure that committee members are representative of all parties to the conflict, trained in dispute resolution and regularly sharing best practices. Cameroon’s international partners, such as the UN and the French development agency, which already have large programs in the area, can help build a functioning system and fund training.

Prevention measures should also address the climate stressors that contribute to inter-communal frictions. Cameroon’s climate change observatory should develop an alert system monitoring critical climate-related issues, in collaboration with regional and sub-regional administrators, as well as related ministries.103 This system could include joint monthly forecasts for precipitation, temperatures and water reserves, assessing their likely impact on agricultural, fishing and pastoral activity as well as on food reserves. Crucially, the government should press relevant ministries to incorporate the observatory’s recommendations into their work, especially when designing the region’s special reconstruction program. At the local level, the monitoring carried out by the observatory would provide administrators with useful data and also help officials in the Far North’s six administrative divisions choose appropriate conflict prevention measures, such as technical advice for farmers, fishers and herders, food assistance to the most vulnerable and targeted patrols by the security forces.

Additionally, with support from international partners, the government should continue to provide humanitarian relief and advocate for increased financial support to meet the basic needs of conflict-affected persons. The government should focus on improving security conditions and social infrastructure in abandoned areas, while allowing displaced people to decide whether they can return safely. Local administrators should work together to provide dignified living conditions for the displaced, even if on a temporary basis. The government, with the support of its international partners, should also begin to prepare for displaced persons’ gradual return and resettlement as security and economic conditions improve.

B.Improving Resilience through Governance, Accountability and Reconstruction

As the threat of immediate violence subsides, the authorities should ease simmering tensions by reducing the harmful impact of poor governance on the already precarious livelihoods of the Far North’s residents.

First, the government’s approach to resource management should be more inclusive. Given the competing authority of local administrators and traditional rulers over land and water allocation, Cameroon’s national government should foster the involvement of a broader array of local representatives in joint consultations on local resource management. Town councils should make sure that existing water management committees have a fair representation of people from the ethnic groups in their areas, as well as women and youth leaders. These committees should oversee the council’s construction and management of water points. International donors and NGOs considering providing development assistance to town councils in these areas should train local officials and traditional rulers in inclusive, participatory approaches to development, which will help rebuild trust. With international support, Yaoundé could also provide pre-deployment training for officials posted to the region, which should focus on the links between climate-sensitive resources, governance and ethnic tensions.

The government should urgently address the existing regulatory shortcomings in laws and practices governing land tenure.Secondly, the government should urgently address the existing regulatory shortcomings in laws and practices governing land tenure. In this regard, it should hasten the adoption of a revised Water Code that sets out which uses of water are to be considered priorities in the event of competing claims on the resource. Meanwhile, national and regional authorities should demarcate grazing corridors as part of the process of clarifying private and public land ownership. These measures may be a drop in the ocean given Cameroon’s complex, chaotic land ownership system. But if accompanied by judicial action that demonstrates zero tolerance for corruption among local officials, they would go some way toward restoring the public’s trust in the state.

Thirdly, Yaoundé should take steps to hold perpetrators of violence to account and build confidence in central and local officials. For example, the government could support the Far North with financing and personnel to conduct thorough investigations into past and present violence, as well as to ensure fair trials for alleged perpetrators, who in many cases have been through a long stretch of pre-trial detention. By delivering justice quickly and impartially, authorities can discourage those who might otherwise keep resorting to organised violence along ethnic lines. In civil matters, the judicial authorities could also use traditional village courts to seek an amicable settlement (locally known in French as accord à l’amiable) between the parties, referring the matter to state courts only if mediation is impossible. In parallel, central authorities should threaten to sanction state officials whose biased land allocation has contributed to communal tensions, unless they opt to work with judicial authorities and affected communities to clarify ownership of disputed land expeditiously.

Restoring people’s rights is unlikely to be enough to end the fighting, however. State courts adjudicating cases that involve violence or dispossession should conduct a thorough assessment of the damages and losses suffered by the victims of the cases they handle. The government, for its part, should set up a victims’ fund to provide individual or community-based compensation that would enable people to resume their income-generating activities or to start new ones. This process should involve consultations with community representatives to increase transparency and avoid inflaming tensions but also to build confidence in the state’s ability to serve its citizens. This form of compensation could help supplement and perhaps eventually replace humanitarian aid. Such initiatives should consider women’s specific losses, such as their farming and fish processing tools and market goods.

The government already has at hand what could be a vitally important stabilisation tool in the special reconstruction program for the Far North.The government already has at hand what could be a vitally important stabilisation tool in the special reconstruction program for the Far North. The program, the details of which Yaoundé is still working out, is an opportunity both to channel extra money to this underfunded region and to ensure that its residents have adequate resources to coexist peacefully, even if the project’s original mandate focuses on repairing the damage wrought by Islamist militant violence.104 Crisis Group has been advocating for increased government engagement in the Far North since 2017, setting out the rationale and guidelines for a reconstruction program for the area.105

As the prime minister’s office works on the program’s design, it should include specific projects to ease water scarcity in the region. For example, the government could clearly demarcate pastures, drill boreholes on land set aside for that use, and develop rules for digging basins on the floodplains of the Logone River. Authorities should involve the experts working for the climate change observatory in devising the region’s special reconstruction program. Given the difficulties of access due to insecurity and poor roads, the government should make every effort to guarantee the equitable delivery of development assistance to the Logone-et-Chari division, including by routing aid through Chad. The government should also ensure that the program committee, made up of representatives from government ministries, includes women and integrates a gender perspective into its activities.

As part of a global commitment to addressing climate change, Cameroon’s international partners and UN agencies, particularly the Development and Environment Programmes, should support Cameroon in improving its climate adaptation strategy. While Yaoundé has focused on climate mitigation and green energy, the Far North offers an opportunity to test a variety of conflict-sensitive climate resilience responses, such as flood management, regulation of fishing canals and innovation in agriculture. Backed by its foreign partners and in collaboration with the LCBC, the Cameroonian authorities should define their adaptation priorities, establish areas for regional cooperation and lobby for funding during international climate negotiations. Preparing this region for future weather shocks could help reduce competition over land and water, thus preventing further conflict in an already troubled area.

V.Conclusion

Cameroon’s Far North is struggling under the strain of conflict exacerbated by climate change, which is triggering disputes over water, land for farming and herding, and river areas for fishing. These resource conflicts between communities have turned deadly in an area already scarred by jihadist insurgencies spilling over from Nigeria. The Choa Arab-Musgum conflict and the threat of other flare-ups of inter-communal violence underscore the need for a multifaceted response that addresses the tensions between ethnic groups fairly and effectively, while tackling the climate-related changes that are intensifying local grievances and resentment.

National authorities have already laid out ambitious investment plans for the north, but these need to be put into effect and built upon. Foreign donors should stand ready to support Cameroon’s efforts to strengthen resource governance, justice and dispute resolution mechanisms, as well as bolster plans to adapt to climate change and expand access to land and water. Given the deterioration in food security in the Far North as well as the humanitarian crisis sparked by fighting and forced displacement, the need for action has become more pressing. Both the government and its international partners should act now to address the roots of growing communal tensions and prevent another wave of violence.