BLOG

January 3rd, 2023

Courtesy of Eurasia Group, a report that water stress is #10 of 2023’s top global risks:

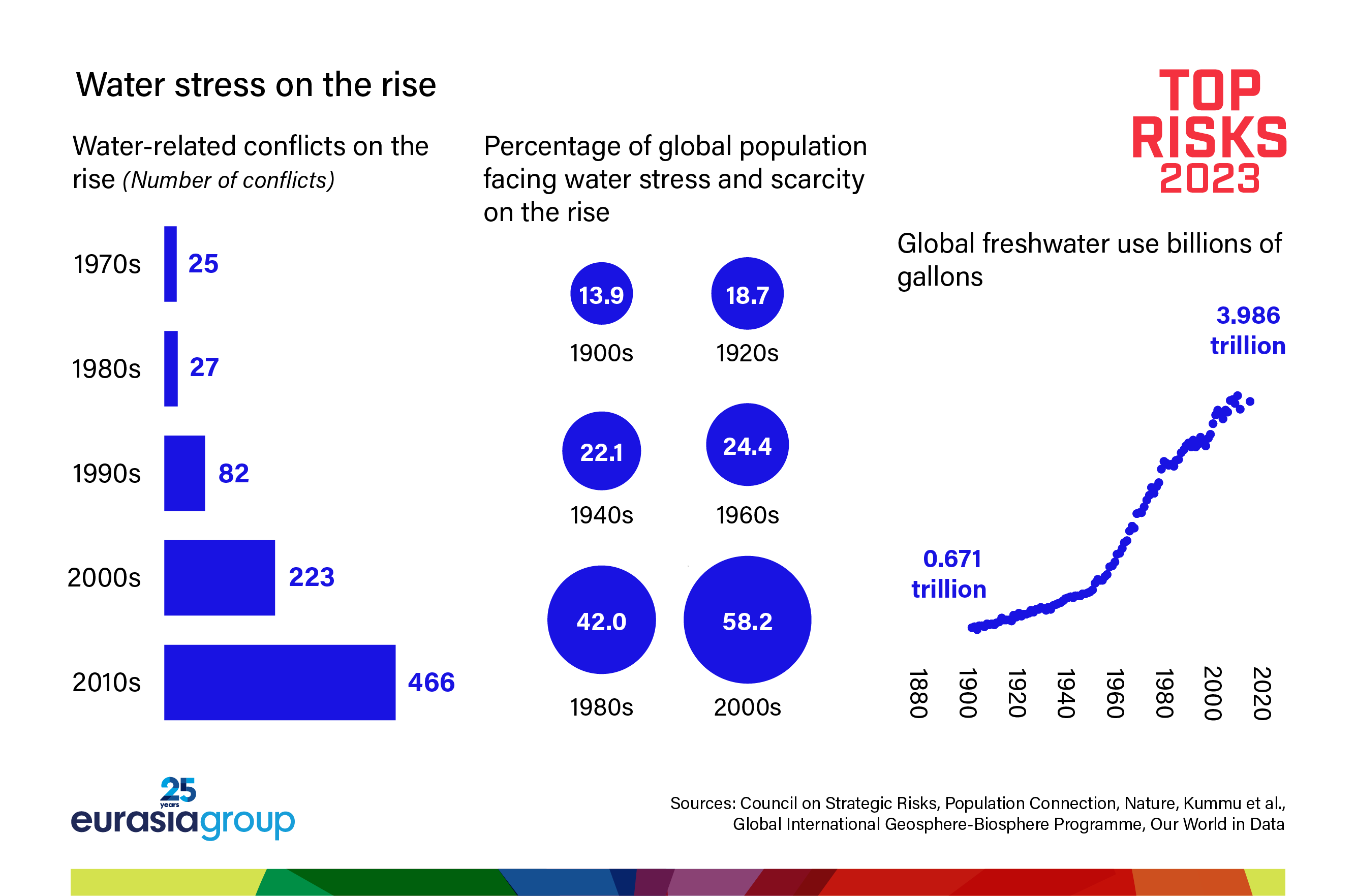

This year, water stress will become a global and systemic challenge … while governments will still treat it as a temporary crisis.In 2022, receding water levels exacerbated the food crisis in Africa, halted shipping and nuclear output in Europe, and led to factory shutdowns in China. Water scarcity also forced the United States to limit water releases in western states and triggered social unrest in Latin America, heightening tensions between corporations and communities. Forecasts for 2023 are worse. Water stress will become the new normal: River levels will fall to new lows, and two-thirds of companies globally will face substantial water risks to their operations or supply chains.Within countries, the number of water-related conflicts, already up sharply since the 1980s, will reach new heights in 2023. The impact will be greatest in the Middle East and Africa, where water will act as a “trigger” in places where militias fight over the scarce resource, and as a “casualty” in places where militants destroy water pumps, tanks, and pipes. Water scarcity will also trigger refugee flows in the Middle East (Syria, Iraq, and Yemen), threaten economic prospects in North Africa (Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia), and heighten food insecurity in the horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia) by driving food prices higher and forcing farmers to migrate. The spillover effects on domestic inequality will increase social unrest in those places where they combine with other economic and social crises, including high inflation, unemployment, disease outbreaks, and energy shortages.

While the consequences of water stress will worsen, governments’ ability to handle them will not improve. Having failed to adequately prepare for a permanent decrease in water availability, policymakers will rely on short-term emergency measures that abruptly restrict and redistribute resources.

US policymakers will have to choose between electricity generation, water releases, industrial production, and food production on the one hand, and water conservation on the other. More US farmers, who will suffer the most from water restrictions taking effect in 2023 (an up to 21% reduction in Colorado River water supplies for some states), will be asked to forgo harvesting to help tackle water scarcity.

Europe will face different challenges. Norway may have to limit electricity exports to preserve hydropower for domestic use, exposing itself to legal challenges from the Netherlands and Germany. And sinking water levels in the Rhine and Po rivers will disrupt inland shipping and hamper broader economic activity in western Europe.

In Latin America, political decisions will push water-intensive industries such as beverage companies to move facilities from dry to water-rich regions. Local policymakers will follow Santiago de Chile’s lead by rotating water cuts among customers, affecting the retail and hospitality industries.

There are no quick fixes in sight. For decades, rich nations treated water scarcity as a problem affecting poor countries that could be mitigated through bilateral aid. This led to chronic underinvestment in technological solutions such as desalination plants, which remain prohibitively expensive for use in agriculture—a sector accounting for 70% of freshwater withdrawals. International cooperation won’t come to the rescue, either. While climate and biodiversity international negotiations—known as conferences of the parties, or COPs—are gaining traction, the COP focused on desertification remains overlooked (have you even heard of it?). The last one in May 2022 made no significant progress. And other global initiatives such as the upcoming UN Water Conference won’t make a dent in water stress this year.Water policy requires a transition from crisis to risk management. That shift will not materialize in 2023, leaving investors, insurers, and private companies to figure out how to handle this challenge on their own.